Dr. Kenneth Wilson is a contributor to the critique of Calvinism that I'm currently reviewing. I'm not up to Wilson's chapter yet in my review, but Thuyen Tran called my attention to a rather glaring error in his chapter/article of the book, and an indication that this was not the first time this error had been seen from Wilson. The error identified was related to a claim by Wilson regarding Irenaeus and the Manichaeans.

In an interview video that Dr. Leighton Flowers posted on February 26, 2019 (link to a few seconds before relevant point of video), Wilson made an interesting claim:

LF: Now did you, in your preparations, did you read through many of these other early church fathers as well?

KW: I did. I have many chapters in my dissertation discussing their views, all talking about original sin, about freedom of will, and the earliest Christians - those guys you just mentioned - Irenaeus, Tertullian and Clement - they're all arguing against Stoics, and against Manichaeans and Gnostics.

Manichaeans were followers of Mani, a 3rd century Persian, who was born around 216 and died around 276. Tertullian died around 220. Irenaeus died around 202. Clement of Rome is believed to have died around 100, while Clement of Alexandria died around 215. None of them had any interaction with Mani or Mani's followers or Manichaeism.

By itself, this off-hand response during a video interview is not particularly troubling. People make slips of the tongue all the time, and while the listed early Christians didn't interact with Mani, they did interact with other heretical, quasi-Christian, and non-Christian groups.

More troubling, though, was the following assertion Wilson makes in the critique to Calvinism edited by Allen and Lemke, and published by B&H academic:

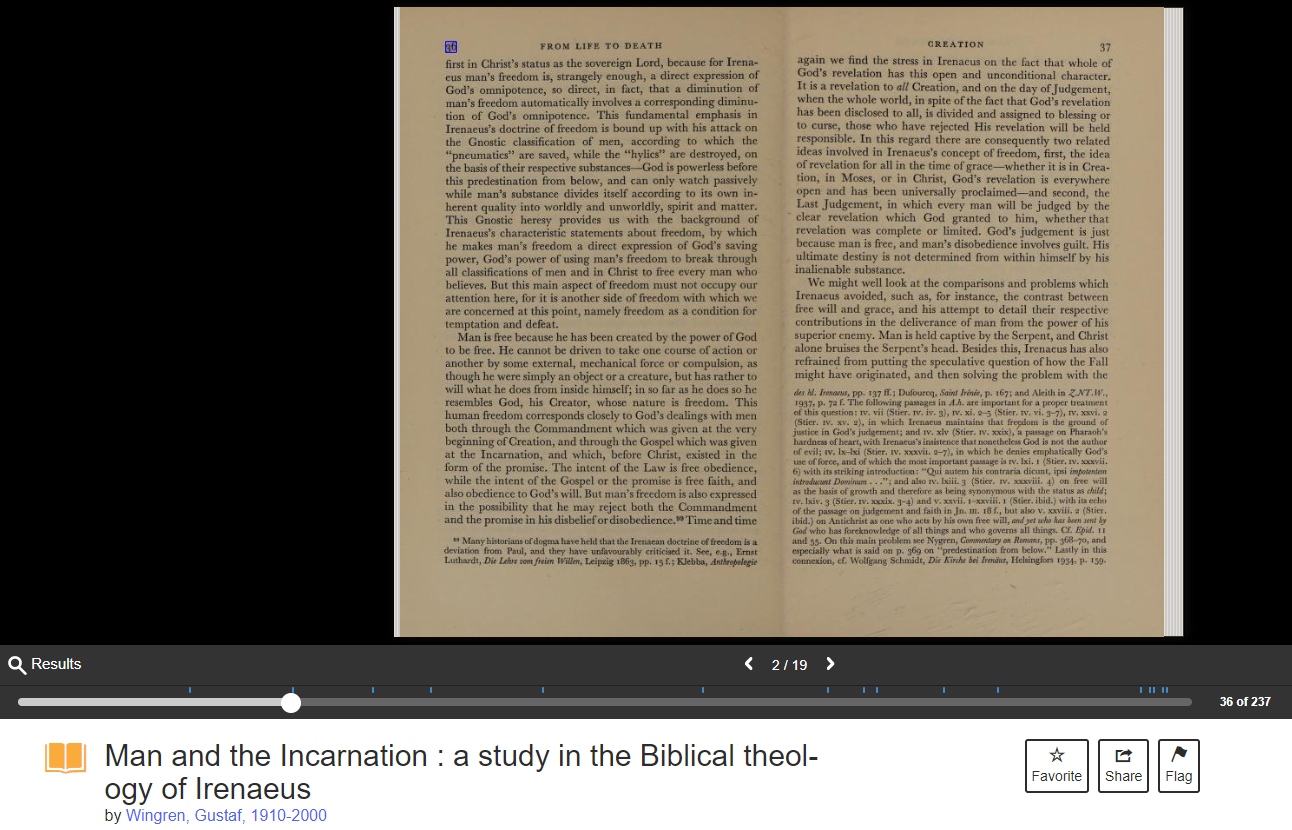

For example, Irenaeus (ca. AD 180) had argued that the Manichaean god was puny because he could only achieve his goals by micromanaging all events and persons. In contrast, the Christian God allowed humanity freedom, yet was so powerful he could still accomplish his plans. It requires a more omnipotent and sovereign God to allow human freedom. "The essential principle in the concept of freedom appears first in Christ's status as the sovereign Lord, because for Irenaeus man's freedom is, strangely enough, a direct expression of God's omnipotence, so direct in fact, that a diminution of man's freedom automatically involves a corresponding diminution of God's omnipotence." (FN17 Gustaf Wingren ... Man and the Incarnation ... pp. 36-37)

One reason this is troubling because obviously Irenaeus was not responding to Mani or the Manichaean god. He correctly notes the approximate date of Irenaeus's Against Heresies. On the other hand, he did not seem to recognize that this was almost a century before the rise of Mani's religion.

Another reason this is troubling is that it is not a correct analysis of Irenaeus. Obviously, interpretations of Irenaeus differ, but even Wilson's source, Wingren, acknowledges that the position that Irenaeus was responding to was not one of divine micromanagement, but exactly the opposite.

Wingren states, in the sentence immediately following that quoted by Wilson:

This fundamental emphasis in Irenaeus's doctrine of freedom is bound up with his attack on the Gnostic classification of men, according to which the "pneumatics" are saved, while the "hylics" are destroyed, on the basis of their respective substances--God is powerless before this predestination from below, and can only watch passively while man's substance divides itself according to his own inherent quality into wordly and unworldly, spirit and matter.

Thus, Irenaeus was not opposing an Augustinian or Calvinistic conception of God's providence, but a position in which God is unable to control. Here's a copy of the relevant pages:

Finally, this is troubling because it appears to be the result of simply recycling source material. This same quotation from Wingren is found in Wilson's book, which itself is apparently essentially his dissertation:

K. Wilson, Augustine's Conversion from Traditional Free Choice to "non-free Free Will" A Comprehensive Methodology, p. 54 (2018).While I appreciate Wilson's attempt to contribute to patristic scholarship, I would encourage him not only to correct this error in any subsequent edition of "Calvinism: a Biblical and Theological Critique," but also to correct his underlying error of thought regarding the relationship of Irenaeus to Augustinian thought.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comment Guidelines:

1. Thanks for posting a comment. Without you, this blog would not be interactive.

2. Please be polite. That doesn't mean you have to use kid gloves, but please try not to flame others, even if they are heretics, infidels, or worse.

3. If you insult me, I'm more likely to delete your comment than if you butter me up. After all, I'm human. I prefer praise to insults. If you prefer insults, there's something wrong with you.

4. Please be concise. The comment box is not your blog. Your blog is your blog. If you have a really long comment, post it on your blog and post a short summary of it here.

5. Please don't just spam. It's one thing to be concise, it's another thing to simply use the comment box to advertise.

6. Please note, by commenting here, you are relinquishing your (C) in your comments to me.

7. Remember that you will give an account on judgment day for your words, including those typed in comment boxes. Try to write so you will not be ashamed if it is read back before the entire world.

8. Stay on topic. If your comment has nothing to do with the post, email it to me (my email can be obtained through my blogger profile), or simply don't post it.

9. Don't post as "Anonymous." If you are going to post anonymously, at least use some kind of recognizable "handle," so we can tell you apart from all the other anonymous folks. (This is moot at the moment, since recent abuse has forced me to turn off "anonymous" commenting.)

10. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you; and abstain from doing to others what you would not wish upon yourself.