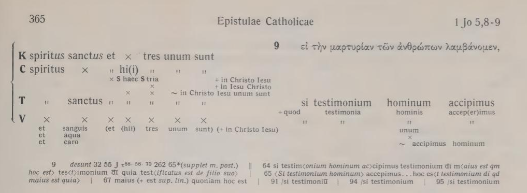

Vetus Latina at 1 John 5:7-8 is very messy.

Friday, June 13, 2025

Vetus Latina at 1 John 5:7-8

Labels: 1 John 5, Johannine Comma, Vetus Latina

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 4:39 PM

Codex Perpinianensis on Revelation 16:5

Codex Perpinianensis is dated to the second half of the 12th century and referred to as "VL 54 (p)." It is available from the French library (link).

The Latin text is:

Labels: Codex Perpinianensis, Revelation 16

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 3:32 AM

Codex Gigas at Revelation 16:5

Codex Gigas is considered an "Old Latin" edition. It contains the following reading for Revelation 16:5:

Et audim angelum quarum dicente Justus es qui es et qui eras et sanctus. quia hec iudiasti

After reading this, I realized how it was that Manetti's Latin has "fourth" instead of "of the water" and that is because of an "a" dropping off in the Latin. Of course "fourth" and "of the water" are not at all visually similar in Greek.

Labels: Codex Gigas, Revelation 16

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 3:32 AM

Death of Antiochus IV according to the books of the Maccabees

2 Maccabees 9 describes Antiochus:

2 Maccabees 9:1-6

About that time Antiochus retreated in disgrace from the region of Persia. He had entered the city called Persepolis and attempted to rob the temples and gain control of the city. Thereupon the people had swift recourse to arms, and Antiochus’ forces were routed, so that in the end Antiochus was put to flight by the people of that region and forced to beat a shameful retreat. On his arrival in Ecbatana, he learned what had happened to Nicanor and to Timothy’s forces. Overcome with anger, he planned to make the Jews suffer for the injury done by those who had put him to flight. Therefore he ordered his charioteer to drive without stopping until he finished the journey. Yet the condemnation of Heaven rode with him, because he said in his arrogance, “I will make Jerusalem the common graveyard of Jews as soon as I arrive there.” So the all-seeing Lord, the God of Israel, struck him down with an incurable and invisible blow; for scarcely had he uttered those words when he was seized with excruciating pains in his bowels and sharp internal torment, a fit punishment for him who had tortured the bowels of others with many barbarous torments.

He initially became even more enraged, but then his flesh started rotting off and:

2 Maccabees 9:12 When he could no longer bear his own stench, he said, “It is right to be subject to God, and not to think one’s mortal self equal to God.”

Then he promised to free Jerusalem and treat the Jews like the Athenians (i.e. with great respect), and even become a Jew himself. But his sufferings did not decrease, so he wrote a letter of supplication to the Jews while at the same time naming his son (also named Antiochus) to be his successor.

After the conclusion of the letter, the epitomizer opines:

2 Maccabees 9:28-29

So this murderer and blasphemer, after extreme sufferings, such as he had inflicted on others, died a miserable death in the mountains of a foreign land. His foster brother Philip brought the body home; but fearing Antiochus’ son, he later withdrew into Egypt, to Ptolemy Philometor.

2 Maccabees 10 then turns to the purification of the temple, and in case you think it's just an unrelated topic, 2 Maccabees 10:9 says "Such was the end of Antiochus surnamed Epiphanes."

This is somewhat different from the account of the death of Antiochus offered in the letter to Aristobulus, contained in the first chapter of 2 Maccabees.

2 Maccabees 1:11-17

Since we have been saved by God from grave dangers, we give him great thanks as befits those who fought against the king; for it was God who drove out those who fought against the holy city. When their leader arrived in Persia with his seemingly irresistible army, they were cut to pieces in the temple of the goddess Nanea through a deceitful stratagem employed by Nanea’s priests. On the pretext of marrying the goddess, Antiochus with his Friends had come to the place to get its great treasures as a dowry. When the priests of Nanea’s temple had displayed the treasures and Antiochus with a few attendants had come inside the wall of the temple precincts, the priests locked the temple as soon as he entered. Then they opened a hidden trapdoor in the ceiling, and hurling stones at the leader and his companions, struck them down. They dismembered the bodies, cut off their heads and tossed them to the people outside. Forever blessed be our God, who has thus punished the impious!

As different as these accounts are, they are also different from the account of the death of Antiochus in 1 Maccabees. In 1 Maccabees, the death of Antiochus is recounted in 1 Maccabees 6, prior to the defeat of Nicanor in 1 Maccabees 7, but after the defeat of Timothy in 1 Maccabees 5.

The story has some similarities to the story from 2 Maccabees 9. The text says:

1 Maccabees 6:1-8

As King Antiochus passed through the eastern provinces, he heard that in Persia there was a city, Elam, famous for its wealth in silver and gold, and that its temple was very rich, containing gold helmets, breastplates, and weapons left there by the first king of the Greeks, Alexander, son of Philip, king of Macedon. He went therefore and tried to capture and loot the city. But he could not do so, because his plan became known to the people of the city who rose up in battle against him. So he fled and in great dismay withdrew from there to return to Babylon. While he was in Persia, a messenger brought him news that the armies that had gone into the land of Judah had been routed; that Lysias had gone at first with a strong army and been driven back; that the people of Judah had grown strong by reason of the arms, wealth, and abundant spoils taken from the armies they had cut down; that they had pulled down the abomination which he had built upon the altar in Jerusalem; and that they had surrounded with high walls both the sanctuary, as it had been before, and his city of Beth-zur. When the king heard this news, he was astonished and very much shaken. Sick with grief because his designs had failed, he took to his bed.

You should notice some similarities to the previous stories. There is reference to a failed temple robbery, although it is in Persepolis in 2 Maccabees and Elam in 1 Maccabees. He does not live and die by his wits as in the Letter to Aristobulus, but instead attempts to use force. News that his forces have been routed reaches him.

The differences, however, are also noticeable. The news he gets includes news that they have purged the temple and rebuilt the temple walls. He is not rotting away in stench but instead is dying from grief and anxiety.

The purification and rededication of the temple is in 1 Maccabees 4 and thus not only before the death of Antiochus, but also before the defeat of Timothy.

In short, remarkably, we have three different accounts of the death of Antiochus in two books (partly because 2 Maccabees is a combination of two introductory letters and an epitome of a history by Jason of Cyrene).

Labels: 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, Apocrypha, Maccabees

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 3:30 AM

Thursday, June 12, 2025

Codex Gigas at 1 John 5:7-8 (And Codex Sangermanensis primus and Codex Colbertinus and Codex Perpinianensis and Book of Armagh

I thought I would check the Vetus Latina manuscripts (a helpful list can be found here) to see what they actually say it when it comes to the Johannine Comma. I should point out that while these manuscripts have been characterized by someone as Old Latin manuscripts and given a "VL" designation, all of these manuscripts are later than Jerome's translation. I am not sure whether anyone has checked/verified whether the text is in fact Vetus Latina, either in general or specifically for the text of 1 John. It is always possible that these manuscripts have been characterized based on having at least one section that is VL, or that they have been mischaracterized. As this is a research-intensive post, it is quite possible that it will be updated from time to time, possibly without formally identifying each update. The initial version of the article covered: VL 6, 7, 51, 54, and 61, of which VL 7, 51, and 61 are witnesses against the JC.

One of the largest and most expensive Bibles ever produced is Codex Gigans, a 13th century manuscript produced in area that is now part of the Czech Republic. It is part of the "Vetus Latina" family and is referred to by the manuscript designation, "VL 51 (gig)." It does not only include Biblical texts but also Isidore of Seville's Etymologies, among other things.

At 1 John 5:7-8, the manuscript has this:

Labels: Book of Armagh, Codex Colbertinus, Codex Gigas, Codex Perpinianensis, Codex Sangermanensis primus, Johannine Comma, Old Latin, Vetus Latina

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 8:46 PM

Tuesday, June 10, 2025

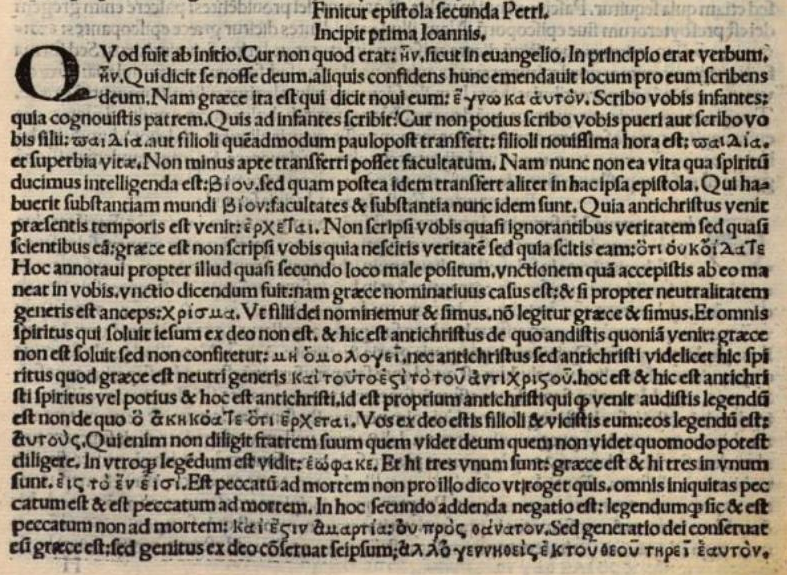

Lorenzo Valla and the Johannine Comma

Lorenzo Valla's annotations on the New Testament, as published by Erasmus, included only about one third of one page on 1 John:

Translation: And these three are one: Greek is And these three are in one. εἰς τὸ ἕν εἰσι (eis to en eisi)

It is interesting that Valla notes the difference between "are one" and "are in one" but does not address the elephant in the room, namely the non-inclusion of "Father, Word, and Holy Spirit." We could speculate about why he does not mention it, but suffice to say that he does not discuss it.

Labels: Johannine Comma, Lorenzo Valla

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 5:34 PM

Giannozzo Manetti and the Johannine Comma

Giannozzo Manetti (1396-1459) was arguably the leading expert on translation from Greek to Latin in the 15th century. His translation of the New Testament remains (as far as I can tell) unpublished. However, (as I've previously discussed here) his manuscripts are available to view online.

Manetti's New Testament at 1 John 5:7-8 has the following:

quia tres sunt qui in caelo testificantur, Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus Sanctus. Et hi tres unum sunt. Et tres sunt qui in terra testificantur: Spiritus, aqua et sanguis

Manetti's Greek source is available. Here is his Greek text:

ὅτι τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες, τὸ πνεῦμα καὶ τὸ ὕδωρ καὶ τὸ αἷμα, καὶ οἱ τρεῖς εἰς τὸ ἕν εἰσιν.

Why, then, does his Latin not agree with the Greek? The short answer is that he was influenced by the Latin text he was aiming to improve.

Here is the Vulgate Latin text from which he was working:

quia tres sunt qui testimonium dant in caelo, Pater, Verbum, et Spiritus Sanctus. Et hi tres unum sunt. Et tres sunt qui testimonium dant in terra: Spiritus, aqua et sanguis

You may note the change that Manetti offers to the Vulgate text: a change from "[they] give testimony" to "[they] testify." It seems to be a more word-for-word translation. However, Manetti skates right past the absence of the JC in the Greek text.

You will note that contrary to the Clementine Vulgate and the KJV, the Latin text agrees with Alcuin's Vulgate (discussed here) against the Clementine Vulgate and KJV/DRB (link) in that it does not include a second instance of "these three are one" after the three earthly witnesses. Again, he has to somewhat ignore his Greek text to do this.

In the previous post, we discussed issues related to Revelation 16:5, where "fourth angel" and "Lord" were included in Manetti's translation on the basis of the Latin, not the Greek (link). So, it should not be very surprising that his Latin "translation" is more of a moderate improvement to an existing Latin text, rather than a fresh translation from Greek to Latin of his actual Greek text.

Labels: Giannozzo Manetti, Johannine Comma, Translation

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 5:20 PM

Monday, June 09, 2025

Alcuin of York and the Johannine Comma

As I was looking for something else, I happened across an image containing the end of 1 John and the beginning of 2 John in a copy of Alcuin's Vulgate Bible. Codex Vallicellianus is apparently representative of a Bible text overseen by Alcuin of York (740-804), at the dawn of the middle ages. The page providing this information must be taken with at least a grain of salt, however, given that the caption of the page image says that one should hover to enlarge the "papyrus" text. It is, of course, not papyrus.

It is quite old, however, and apparently a copy of a recension of the text by one of the leading scholars of Western Christianity at the time. Most interesting to me, it follows the Greek rather than the interpolation found in the King James Version at 1 John 5:7-8.

Labels: Alcuin, Johannine Comma

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 6:59 PM

Isidore on Hebrew as the Original Language

Isidore of Seville (560-636) is one of the most influential western theologians of the late patristic period. He was a noted linguist, but his views do lean toward the idea that Hebrew was the language spoken in the garden of Eden by Adam and Eve, and that all the language confusion at Babylon was various departures from Hebrew. Here are some examples of his statements on this point:

Etymologies, Book IX, number 1:

Language diversity began after the flood, during the construction of the tower. The arrogance of that tower divided human society: different words had the same meaning. Earlier, all nations used one language: Hebrew. The patriarchs and prophets used it for speech, as well as for their holy writings. ...

Etymologies, Book X, number 191:

Nugas is a Hebrew word. It is set out in the books of the Prophets, where Zephaniah (3.18) says, Nugas, qui a lege recesserunt (the sorrowful, who have withdrawn from the law), enabling us to know that the mother of all languages is Hebrew.

(I should note that the parenthetical is from the translator.)

Etymologies, Book XII, number 2:

The pagans gave names to each animal, in their own languages. Adam assigned names using neither Latin, Greek, or the barborous tongues of the pagans, but Hebrew, the universal language before the flood.

I have recently heard folks begin to discuss this view with the label "Edenics." Having only found that term in Wikipedia dictionaries, I'm a little reluctant to endorse it as having an established meaning, but - at any rate - this view by Isidore seems to fit the description of that label.

It's interesting to note that Isidore also makes an argument for the use of multiple versions (in multiple languages) based on the potential obscurity of the Scriptural language.

Etymologies, Book IX, number 3:

The sacred languages are pre-eminent throughout the world: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. These three languages were used by Pilate to write the charge <"King of the Jews"> against the Lord at the top of the cross. The obscurity of the Holy Scriptures, makes knowledge of these languages necessary. When the wording of one language creates doubt about a word or meaning, there is recourse to another.

The above translations come from Priscilla Throop's translation (2005 for books I-X and 2006 for books XI to XX).

Labels: Edenics, Hebrew, Isidore of Seville

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 2:22 PM

Sunday, June 08, 2025

Isidore of Seville on Dragons

Isidore of Seville (560-636) is one of the most influential western theologians of the late patristic period. One of his major scholarly focuses was the meaning of Latin words. So, I was fascinated by his discussion of the Latin word for Dragon, Draco. What I find particularly interesting is that none (or at least very few) of the late medieval characteristics of dragons are reflected in Isidore's description. Instead, his description just seems to be of a gigantic snake, like an anaconda, particularly one that is religiously venerated.

Book of Differences, I, 48 (p. 97)

The difference between words for snake (anguis, serpens, and draco) is that angues are in the sea, serpentes are on land, and dracones are in a shrine. As Virgil says (Aeneid 2.203-204) "Angues through the peaceful depths"; and a little further on (2.214) "Each serpens embraced"; and (2.225) "Dracones to the lofty shrines".

Etymologies, VIII, Topic 11, 55

The say Apollo is also called Pythius, from Python, the serpent of immense size, whose poison was as terrifying as his size. Piercing him with arrows, Apollo felled him, and carried back the spoils, including the use of his name, so he is called Pythius. He also instituted the celebration of the Pythian rites, to honor the victory.

Etymologies, XII, Topic 4, 4

The dragon or python, draco, is larger than all serpents, as well as all animals on earth. The Greeks call it δράκων, whence it becomes draco in Latin. It is said to be often drawn from its den into the air, which is stirred up because of him. He is crested, with a small face, and narrow tubes through which he draws his breath and moves his tongue. His power is not in his teeth, but in his tail, and he kills with a lash, rather than with his gaping jaws.

Etymologies, XII, Topic 6, 42

The sea dragon, draco marinus, has stingers on its arms, facing its tail. When they strike, poison pours into whatever is hit.

Etymologies, XVIII, Topic 3, section 3

Standards of snakes, dracones, were started by Apollo, with the death of the serpent Python. From that time, they began to be carried in war by Greeks and Romans.

Labels: Dragons, Isidore of Seville

Published by Turretinfan to the Glory of God, at 9:01 PM