Introduction

This post is to provide some written responses to a few interesting issues that have arisen in the wake of a recent Purgatory debate (and preparation for that debate). As the post has evolved a bit since its initial posting, I'm going to try to clean it up and make it more user-friendly, as well as incorporate the best arguments from the other side and my responses to those arguments. I don't disagree with the other side about everything, so it's not an entirely a matter of just disputing everything said on the other side, but nevertheless I think it is overall an edifying exchange.

The date of the current update is October 2, 2024.

Executive Summary

David Szárász, responding to a recent video on 2 Maccabees 12, asked:

1. What is the significance of all this "issue". Or why would that matter if 12:43-45 was not Jasonic? Or how does this undermine anyhow anything in regards to purgatory?

2. What is the evidence that 12:43-45 is not Jasonic if we don't have Jason's 5-Volume work?

For context, these are the related videos in reverse chronological order:

1. Explaining the Source Critical (and Text Critical) Issue at 2 Maccabees 12:43-45

September 16, 2024

2. The Great Purgatory Debate | William Albrecht vs. TurretinFan - Is Purgatory Biblical & Ancient?

September 14, 2024

3. Further Thoughts on 2 Maccabees 12 September 14, 2024 (very shortly before the debate)

4. How does 2 Maccabees 12 undermine Purgatory? August 6, 2024

David's comment is on the most recent video (i.e. video 1 in the above list). I appreciate this thoughtful comment, which asks several important questions.

The main issue identified in video 1 is a question of source criticism, namely a question of how the final form of the Greek text came into existence based on a variety of sources. There is also an ancillary issue of a notable textual variant in which the Latin version departs from the Greek.

Source Issues

The book of 2 Maccabees explicitly relies on at least one pre-existing source. For example, 2 Maccabees 2:23 (NETS) states: "all this, which has been set forth by Jason of Cyrene in five volumes, we shall attempt to condense into a single book." This preface concludes at 2 Maccabees 2:32 (NETS) "At this point, therefore, let us begin our narrative, while adding just this to what has already been said; for it would be foolish to lengthen the preface while cutting short the narrative itself." Indeed, the preface acknowledges that editorial task was laborious (2 Maccabees 2:26 (NETS) "For us who have undertaken the toil of abbreviating, it is no light matter but calls for sweat and loss of sleep") and that various liberties were taken (2 Maccabees 2:32 (NETS) "but the one who recasts the narrative should be allowed to strive for brevity of expression and to forego exhaustive treatment.").

Likewise, 2 Maccabees 15:37-38 (NETS) states:

37 This is how it went with Nicanor, and from that time the city has been ruled by the Hebrews. So I myself will here bring my story to a halt. 38 If it is well written and elegantly dispositioned, that is what I myself desired; if it is poorly done and mediocre, that was all I could manage.

The unknown author who writes the "preface" in chapter 2 and the conclusion at the end of chapter 15 is necessarily not Jason. We refer to this person as the epitomizer.

It appears that the epitomizer's work begins at 2 Maccabees 2:19 (NETS) "The story of Ioudas Makkabaios and his brothers and the purification of the greatest temple and the dedication of the altar ... ."

The work of the epitomizer is presented as an attachment to a letter described as being "The people of Hierosolyma and of Judea and the senate and Ioudas, to Aristobulus, who is of the family of the anointed priests, teacher of King Ptolemy, and to the Judeans in Egypt, greetings and good health" (NETS 2 Maccabees 1:10b) Moreover, that letter together with the work of the epitomizer is presented as attachments to a letter that introduces the book: "The fellow Judeans in Hierosolyma and those in the land of Judea, to their Judean brothers in Egypt, greetings and true peace." (NETS 2 Maccabees 1:1)

There is some speculation that the letter purporting to be from Ioudas is effectively a forgery by the author of the letter from the Judeans. In terms of source criticism, it's simpler to consider that the two letters have the same author, although being more generous to the book, they would have two different authors.

Taking the simpler assumption we have:

- Jason of Cyrene

- The Epitomizer

- The Author of the Letters

We assume for simplicity that Jason composed his account as an original work. Then, the epitomizer summarized Jason's work, perhaps adding his own editorial thoughts at various points and perhaps adding information from other sources. Finally, the Jerusalem Judeans who wrote the letter may have made edits of their own when adapting the underlying work to their purpose.

In the introduction to the NETS edition of 2 Maccabees, Joachim Schaper explains (as I discussed in video 1):

Any critical edition of 2 Makkabees relies mainly on two famous Greek uncial manuscripts: the Codex Alexandrinus (fifth century) and the Codex Venetus (eighth century). There is also a rich tradition of Greek minuscule manuscripts, as well as manuscript witnesses to Syriac, Armenian and Latin transla- tions. There also is a Coptic fragment of some passages from 2 Makk 5-6. [FN 1] Hanhart's edition is based mainly on Alexandrinus and on minuscules 55, 347 and 771.

The body of the text of 2 Makkabees, that is, 3.1-15.36, is a literary creation in its own right without a Hebrew parent text. It is an epitome drawn from the five-volume work of Jason of Cyrene produced by an epitomator who introduces the results of his labors in the prooemium found in 2.19-32. In 1.1-10a and 1.10b-2.18 two letters referring to the feast of Succoth in the month of Kislev are made to introduce the main part. The letters most likely are translations of Hebrew or Aramaic originals, but the parent texts are not known. An epilogue, which was produced by the epitomator, follows in 15.37-39.

The main body of the text (3.1-15.36) goes back to Jason of Cyrene, the author whose five-volume history was abbreviated (or "epitomised"). However, Jason could not possibly have produced some passages: 4.17; 5.17-20; and 6.12-17. The epitomator authored them. The whole of chapter 7, 12.43-45 and 14.37-46 also seem alien in the context of Jason's history.[FN 2] Furthermore, two versions of the Heliodorus narrative exist side by side in chapter 3. Version A, as identified by E. Bickerman (3.24, 25, 27, 28, 30),[FN 3] must have been produced by a post-Jasonic author.[FN 4]

As this section notes, one of the places where the final form of the work appears to depart from Jason's work is at 12:43-45. Specifically:

43He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand drachmas of silver, and sent it to Hierosolyma to provide for a sin offering.

In doing this he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection. 44For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. 45But if he was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Therefore he made atonement for the dead so that they might be delivered from their sin.

The first level of indent seems to be Jason's original report. It has an essentially neutral tone, and merely reports what happens. The second level of indent seems to attempt to justify/explain the behavior described by Jason.

The most natural explanation of the sin offering (ignoring the explanation from 43b onward) is that the intent was to remove corporate guilt for the sin of the idolatrous soldiers. It seems that the epitomizer (or perhaps the Judeans) has a more individualist understanding of sin, such that it does not cross their mind that the offering is for corporate guilt. This person finds an offering for the sins of dead people an oddity. Nevertheless, the person comes up with a possible justification for the action based on belief in the resurrection of the righteous. This explanation is one that is consistent with Pharisee theology, though not with Sadducee theology.

As noted above, one of the parts of 2 Maccabees that seems foreign to Jason is the entirety of chapter 7. This chapter contains another theological statement about resurrection in the mouth of one of the martyrs:

2 Maccabees 7:13-14 (NETS)

13 After he too had died, they maltreated and tortured the fourth in the same way. 14When he was near death, he said, “It is desirable that those who die at the hands of human beings should cherish the hope God gives of being raised again by him. But for you there will be no resurrection to life!”

Assuming that whoever included 2 Maccabees 7:14 also included 12:43-45, then the motive for the offering takes on a specific meaning. According to 2 Maccabees 7:14, the resurrection to life is not for everyone. Thus, the motive for the sin offering is to make sure that the idolatrous soldiers can join in the resurrection to life.

However, under the Roman Catholic conception of Purgatory, everyone who is in Purgatory is already guaranteed participation in the resurrection to life.

The further undermining of Purgatory is that the epitomizer does not even think of the possibility of Purgatory in explaining the offering. According to the text, if there were no resurrection, this would be a pointless sacrifice. However, in Roman Catholic theology souls can escape from Purgatory before the resurrection. Thus, even if there were no resurrection, there could be benefit. In short, the author's argument depends on being unaware of Purgatory as such.

Text Issues

As mentioned in the video, there is also a further issue that the Vulgate Latin does not fully align to the Greek text and accordingly does not accurately render the text.

Thus, the Douay-Rheims English has:

43-46 (1889 ed.) And making a gathering, he sent twelve thousand drachms of silver to Jerusalem for sacrifice to be offered for the sins of the dead, thinking well and religiously concerning the resurrection, (For if he had not hoped that they that were slain should rise again, it would have seemed superfluous and vain to pray for the dead,) And because he considered that they who had fallen asleep with godliness, had great grace laid up for them. It is therefore a holy and wholesome thought to pray for the dead, that they may be loosed from sins.

43-46 (1610 ed.) And making a gathering, he sent twelve thousand drachmes of silver to Jerusalem for sacrifice to be offered for sin, well and religiously thinking of the resurrection. (For unless he hoped that they that were slain should rise again, it should seem superfluous and vain to pray for the dead.) And because he considered that they, which had taken their sleep with godliness, had very good grace laid up for them. It is therefore a holy, and healthful cogitation to pray for the dead, that they may be loosed from sins.

By contrast, translations based on the Greek have (note that the versification is different):

(NETS) 43-45 He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand drachmas of silver, and sent it to Hierosolyma to provide for a sin offering. In doing this he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection. For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Therefore he made atonement for the dead so that they might be delivered from their sin.

(Ehorn) 43-45 And after making a collection from every man, he sent about two thousand drachmas of silver to Jerusalem to offer a sacrifice concerning sins, acting very rightly and honorably, considering the resurrection. For, if he were not expecting those who had fallen to rise, it [would be] superfluous and frivolous to pray for the dead. And if [he was] looking to a most splendid reward for those who fell asleep in godliness, the thought was holy and pious. Therefore, he made atonement for the dead to release [them] from sin.

(Doran) 43-45 Consequently, he made a collection from each man, and he sent about 2,000 silver drachmas to Jerusalem to bring a sacrifice for sin. He acted very correctly and honorably as he considered the resurrection. For if he were not expecting that the fallen would rise, [it would have been] superfluous and silly to pray on behalf of the dead. If he was looking at the most noble reciprocation placed for those who fall asleep piously, the thought was holy and pious. Wherefore, concerning the dead he made atonement to be absolved from the sin.

(Schwartz) 43-45 After making a collection for each man, totaling around 2000 silver drachmas, he sent it to Jerusalem for the bringing of a sin-offering – doing very properly and honorably in taking account of resurrection, for had he not expected that the fallen would be resurrected, it would have been pointless and silly to pray for the dead – and having in view the most beautiful reward that awaits those who lie down in piety – a holy and pious notion. Therefore he did atonement for the dead, in order that they be released from the sin.

(NEB) 43-45 He levied a contribution from each man, and sent the total of two thousand silver drachmas to Jerusalem for a sin-offering - a fit and proper act in which he took due account of the resurrection. For if he had not been expecting the fallen to rise again, it would have been foolish and superfluous to pray for the dead. But since he had in view the wonderful reward reserved for those who die a godly death, his purpose was a holy and pious one. And this was why he offered an atoning sacrifice to free the dead from their sin.

(RSV) 43-35 He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand drachmas of silver, and sent it to Jerusalem to provide for a sin offering. In doing this he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection. For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. Therefore he made atonement for the dead, that they might be delivered from their sin.

(Brenton's) 43-45 43 And when he had made a gathering throughout the company to the sum of two thousand drachms of silver, he sent it to Jerusalem to offer a sin offering, doing therein very well and honestly, in that he was mindful of the resurrection: for if he had not hoped that they that were slain should have risen again, it had been superfluous and vain to pray for the dead. And also in that he perceived that there was great favour laid up for those that died godly, it was an holy and good thought. Whereupon he made a reconciliation for the dead, that they might be delivered from sin.

(KJV 1611) 43-45 And when he had made a gathering throughout the company, to the sum of two thousand drachmes of siluer, hee sent it to Ierusalem to offer a sinne offering, doing therein very well, and honestly, in that he was mindfull of the resurrection. (For if he had not hoped that they that were slaine should haue risen againe, it had bin superfluous and vaine, to pray for the dead.) And also in that he perceiued that there was great fauour layed vp for those that died godly. (It was an holy, and good thought) wherupon he made a reconciliation for the dead, that they might be deliuered from sinne.

Notice that the underlying Latin to the DRB differs (a) by suggesting that those who had died had died in godliness, (b) by endorsing prayer for the dead, rather than just reporting prayer for the dead, (c) by indicating 12000 drachmas rather than 2000 drachmas, and (d) by substituting prayer for atonement/reconciliation.

In at least some of the videos, I mention the Peshitta version of 2 Maccabees. While one often finds folks trying to argue for Aramaic primacy, the Aramaic is a translation of Greek. For example, in his introduction to, "The Antioch Bible: The Syriac Peshitta Bible with English Translation," Philip Michael Forness states:

The four books of Maccabees likewise were not part of the original Peshiṭta translation of the Old Testament.

The Second Book of Maccabees was written in Greek and contains a compilation of texts from the second century BCE. One of the texts was likely written in Aramaic originally, but it was translated into Greek in the final form of this work.

...

The Peshiṭta Syriac translation (= P) of the Second Book of Maccabees is based on the Lucianic recension of the Septuagint Greek text (= LXX). Many differences between the versions attest to the translators’ efforts to make the content intelligible in Syriac while freely rendering the Greek. A close comparison of the Peshiṭta and Septuagint versions of this work reveal differences due to the free style of translation: additions to lists of items or actions, specifications or omissions of names, transformations of subordinate clauses in Greek into separate sentences in Syriac, etc. Yet, some of these differences reflect the basic features of translation criticism: mistranslation, inner-Syriac corruptions, and deliberate changes.

"Appendix 2: Variant Readings" provides the following for 12:43

Finally, here is the (at least a little dynamic) translation of the Peshitta version:

43 He made the whole nation donate silver, collecting three thousand[FN 1] pieces of silver.[FN2] He sent them to Jerusalem so that they might make offerings for their sake. He acted justly and righteously for the hope of the resurrection from the dead. 44 For if he were not waiting and expecting the resurrection from the dead, this would be foolishness and folly that someone would pray and make offerings on behalf of the dead. 45 He was looking for and waiting for the wages, hope, and rest that is prepared for those who fall asleep in righteousness. 46 For this reason, he sent for them to make atonement for the sins of those who had fallen asleep.

[FN1] ‘three thousand’ reflects the Lucianic recension.

[FN2] ‘pieces of silver’: lit. ‘silver’.

Notice the seeming attempted correction of two thousand to three thousand (because Judas Maccabeus had three columns of troops). Notice also that while the Peshitta likewise moves from tentative endorsement to endorsement of Judas' acts, though without the broader endorsement of the entire category of prayer for the dead.

Finally, I should add (for the sake of being thorough), that we lack any early attestation of 2 Maccabees 12:43-45. I believe that the first manuscript evidence (for that passage) is the fourth century and there do not seem to be any Jewish or Christian quotations of that portion of the text before Augustine. Could this be an early Christian interpolation to the text? I think it would be hard to prove that it was not such an interpolation. That said, I think it would be absurd to insist that it must be a Christian interpolation, or even to suggest that the probabilities favor such a conclusion. At most, for now, it seems it remains a hypothetical possibility.

David Szárász's Questions Answered

Returning to David Szárász's questions:

What is the significance of all this "issue".

As to the question, I suppose that there may be two answers: one from William's perspective (who made it a focus of cross-examination) and one from my perspective.

From William's perspective, I'm not sure. I don't know why it matters to William whether the text was Jasonic, the work of the epitomizer, or the work of the Judeans at Jerusalem. Presumably, it is the final form of the text that William thinks is authoritative, and (aside from rejecting the Latin corruptions) I don't dispute what the final form of the text is.

From my perspective, it's valuable background for understanding the motivation of the text - the formation of the final form of the text explains the significance of the text to the author. Understanding the author's intent helps us rightly interpret the words that are used.

Nevertheless, if I were to conclude that Jason himself wrote 12:43-46, my analysis would not be significantly different. The author is questioning why Judas Maccabeus did what he did, and attempting to find a reasonable explanation for it. The focus on the resurrection as the reason would suggest that Jason had proto-Pharisaic (as opposed to proto-Sadducean) theological tendencies. Nevertheless, under either explanation the author seems puzzled by the sacrifice, tries to provide an explanation for it, and arrives at an explanation that is resurrection-focused. This means that the author not only wasn't writing about Purgatory, but did not even have Purgatory in mind as a possible reason for why the sacrifice was to be offered.

Returning to David Szárász's questions:

Or why would that matter if 12:43-45 was not Jasonic?

If we think that the epitomizer added his comment at this portion, it explains the reason that a sacrifice is treated as a category of "prayer." Diaspora Jews did not have regular access to the temple sacrificial system, so their worship primarily consisted of prayer. I don't think this explanation has enormous bearing on the points raised above, for the reasons already explained above.

If we think that the Judeans of Jerusalem added their comment at this portion, it explains the very large cost of the sacrifice. The Judeans of Jerusalem are also more likely to be interested in the debate over the resurrection, and particularly more interested in treating Judas Maccabeus as though he were a proto-Pharisee. There is some puzzling misquotation (or misinterpretation) of the Old Testament in the letters that the Judeans added:

2 Maccabees 2:11 (NETS) And Moyses said, “They were eaten up because the sin offering had not been eaten.”

2 Maccabees 2:11 (KJV) And Moses said, Because the sin offering was not to be eaten, it was consumed.

There does not seem to be any such statement in the Torah. There were offerings that were not to be eaten (see Leviticus 6:23&30 for example), but that does not seem to be the explanation provided at Leviticus 9:22-24, describing the event to which the Judeans' letter seems to be referring. It seems to be some kind of conflation of that account with the account of Leviticus 10:16-20 (or perhaps something else - the reference is very unclear).

Given such conflation, it is possible that the Judeans were not highly precise in their understanding of the Torah, and consequently did not understand the real reason (i.e. corporate guilt) for which Judas Maccabeus offered the atonement offering. This then explains their need to provide the explanation we see.

Nevertheless, whether it is the epitomizer or the Judeans (or some other editor), I don't think it substantially affects the underlying point that the person who wrote this did not even think of Purgatory, much less intend the text to have some reference to Purgatory.

Returning to David Szárász's questions:

Or how does this undermine anyhow anything in regards to purgatory?

In itself, I don't think it does. The problem is approximately the same regardless of who composed the final form of 2 Maccabees 12:43-45.

I suppose that on the hypothesis that it did, in fact, teach purgatory, having it be Jasonic would make it a very slightly older testimony. It's believed that Jason wrote close to the events, that the epitomizer epitomized not long after Jason wrote, and that the Judeans adopted the epitome within a matter of decades (as opposed to centuries).

By contrast, therefore, because the text shows no knowledge of Purgatory (and is contradictory to Purgatory), I suppose it is very slightly more significant that this edit may have been made as late as the Judeans' letter (or potentially even later, though I must emphasize that I'm merely mentioning this for the sake of being thorough, not because I think we should assume subsequent editing).

Returning to David Szárász's questions:

2. What is the evidence that 12:43-45 is not Jasonic if we don't have Jason's 5-Volume work?

It's important to distinguish between evidence and proof. As far as we know, Jason's work is lost. Therefore, proving that something is not Jasonic is a challenge. When the NETS introduction argues that our passage seems foreign to Jason, it provides footnote:

2 See the arguments put forward by C. Habicht, 2. Makkabäerbuch (Jüdische Schriften aus hellenistisch-römischer Zeit I/3; Gütersloh: G. Mohn, 21979 [1976]) 171.

It might be valuable to consider those arguments. For myself, I find Schwartz's arguments convincing. For example, at p. 24 in the introduction of his commentary, Schwartz states:

Our conclusion is that the two martyrologies of 6:18–7:42, although originating in a source or sources different from that which supplied the rest of the book, were inserted into it by whoever put the book into its present form – more particularly, by whoever undertook to speak with an authorial first-person voice in the three sets of reflections at 4:16–17, 5:17–20 and 6:12–17.

Who in fact speaks as an author in those sets of reflections – Jason or the epitomator? It seems clear that we must assume, as is usual, that it is the epitomator, i.e. he who speaks to us in 2:19–32 and 15:37–39. This results, first and foremost, from the use of the first person in 6:12, 15–16 – just as it is used by the epitomator in 2:19–32 and 15:37–38. Having used the first person to introduce himself as an epitomator in Chapter 2, it would be dishonest, if not impossible, for that writer to pass on someone else’s first person in Chapter 6.

Schwartz then goes on to provide a number of detailed arguments in support of his point. At p. 25, Schwartz transitions:

At this point, having traced 3:1–6:17 (apart from the Heliodorus story and the authorial reflections at 4:16–17, 5:17–20 and 6:12–17) along with Chapters 8, 14–15 to the basic work (Jason), 6:18–7:42 to a separate source incorporated by the author, and 10:1–8 to the Jerusalemites who turned the book to their own purposes (and added in the two opening epistles), we must turn to Chapters 9–13. These chapters constitute, from the point of view of the historical narrative, the roughest part of the book.

A lot of Schwartz's arguments are focused on trying to unravel multiple issues in the flow of the text in terms of itself and in terms of the parallel accounts in 1 Maccabees. By page 30, he writes:

Having discussed the original order of Chapters 13, 12, 9, we must now turn to Chapters 10–11. These two chapters, even apart from 10:1–8 (which we have attributed to post-authorial Jerusalemite editing), are quite different from those around them.

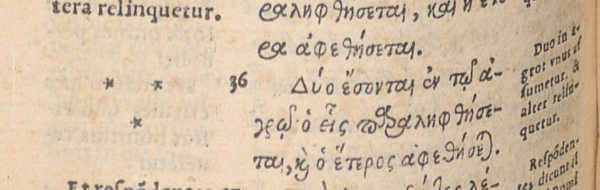

At p. 443, Schwartz analyzing the words of the text writes:

a holy and pious notion ([Greek text]). These words constitute a note within a note and sound secondary (esp. in light of the similar comment in v. 43); for the suggestion that they have been added from some marginal note, see G. C. Cobet, Variae lectiones (Lugduni-Batavorum: Brill, 18732) 480, who compares a similar comment frequently excised by editors of Plato’s Republic 504E. See also Niese, Kritik, 110, n. 3 and Katz, “Text,” 20–21.

Doran in his commentary, 2 Maccabees, p. 246, discussing 43b-45a, wrote:

This section has been the subject of much discussion. ... Elmer O'Brien[FN61] and Abel see these two sentences as the result of several glosses made to an original text and follow the Latin text of LAᴸ: "because [reading ὄτι instead of εἰ μὴ γάρ he hoped that the fallen would rise (superfluous and silly to pray for the dead), considering that the best reward was reserved for those who die piously (a holy and pious thought)." The phrases in parenthesis would have been made by later editors, the first by a skeptical reader, the second by someone who believes in the resurrection. However, I have chosen to follow the text as found in Hanhart's critical edition and see the two conditional sentences balancing one another. As in previous reflections, the author counters opposing positions, as in 5:18 and 6:12-13. Here the author first refutes the opinion that it is pointless to pray for the dead and then encourages people to live and die piously.

[FN 61 Elmer O'Brien, "The Scriptural Proof for the Existence of Purgatory from 2 Machabees 12:43-45," Sciences ecclésiastiques 2 (1949) 80-108.

In his introduction, p. 3, Doran notes: "As Schwartz has noted, there is little evidence that the work was known by Philo, Josephus, or the rabbinic tradition." Doran cites pp. 85-90 of Schwartz. The cited section is Section VI "Reception and Text." That section begins thus (pp. 85-86 footnote omitted):

1. Who Read 2 Maccabees? 2 Maccabees was written with Jewish readers in mind, and although we may occasionally discern hints that the author – if not some copyist – took non-Jewish readers into account, it is not at all surprising that prior to the rise of Christianity there is no evidence for non-Jewish readers. After all, “the fact … is that the translation of the Holy Scriptures into Greek made no impression whatever in the Greek world, since in the whole of Greek literature there is no indication that the Greeks read the Bible before the Christian period.” But there is not much evidence for Jewish readers either. True, the book was transmitted as part of the Septuagint, and the letters appended to its beginning indicate that official Jerusalem, of the Hasmonean period, encouraged the Jews of the Diaspora to read it.196 Nevertheless, until the late first century C.E. (at the earliest) we know for sure of only one Jewish reader of our book: the author of 4 Maccabees, who retells at length the martyrdom stories of 2 Maccabees and also includes a version of the Heliodorus story. Philological comparison leaves virtually no room for doubt about its use of our book.

As for other possible Jewish readers, there is not much to discuss. In all of Philo’s corpus there is, it seems, only one passage which might indicate knowledge of 2 Maccabees, and even that passage (That Every Good Man is Free, 89), which alludes to cruelty and torments, lacks any very specific pointers to our book. Josephus seems clearly – given both what his books do include and what they do not include – not to have known 2 Maccabees. True, there are a few tantalizing points at which he agrees with its story, even against his major source (1 Maccabees), but in the absence of common errors or the like there is little reason to suppose that he got his material from our book in particular. Growing up in Jerusalem he could have learned details of the Jewish side of the story (such as the fact that those who fled to caves were burned [6:11]) from any number of sources, and as for details of Seleucid history (such as the fact that Demetrius arrived in Syria specifically at Tripoli [14:1]), we know that he had access to detailed material on that dynasty and its history. As for 3 Maccabees, here the picture is less clear, for it has much in common with 2 Maccabees, beginning with numerous words and including Temple-invasion stories (2 Macc 3//3 Macc 1–2) that are quite similar one to another. Nevertheless, given the fact that it tells a different story even in this case it is difficult to infer dependence, and since although 3 Maccabees is a later book its Temple-invasion story appears to be simpler (= more original?) than that of 2 Maccabees, it seems wiser to ascribe the similarities to a common cultural background, and perhaps to common traditions, than to literary dependence.

Schwartz goes on to speculate regarding why the Jewish usage of the book seems to be so little. He then turns to Christian usage, which is focused on the accounts found in chapters 5-7. Finally, returning to Rabbinic literature, at p. 90 Schwartz writes:

Rabbinic literature and medieval Jewish literature, in contrast, show next to no interest in our book (as most of apocryphal literature). True, the story of the mother and her seven sons may be found in several works, but – as we have seen even with regard to 2 Maccabees itself (above, pp. 19–20) – it had a life of its own, so there is no need to trace Jewish retellings of the story to our book, especially given the fact that it was in Greek and they were in Hebrew. Josippon, a tenth-century Jewish version of Josephus which quite obviously used some version of 2 Maccabees, is a striking exception.

All of this to suggest that if there was any tinkering with the text after what I've been referring to as the final form (presumably in the 2nd century BC), then the most likely culprits would be Christian copyists.

As with much source criticism, the evidence is not strong enough to rise to the level of definitive proof, at least from what I've seen. Perhaps Elmer O'Brien has more to say on the subject, but I have not (as of my initial publication of this blog post) looked deeper into the subject.

The passage (43b-45a) stands out like a sore thumb in comparison to the neutral reporting that seems to characterize most of the material apparently epitomized from Jason. Although defensive of Judas' actions, it does not seem to a reflect a first-hand understanding of the actions.

Appendix: New American Bible, Revised Edition (link to source)

The New American Bible, Revised Edition has the following text (versification aligning to the Vulgate):

43 He then took up a collection among all his soldiers, amounting to two thousand silver drachmas, which he sent to Jerusalem to provide for an expiatory sacrifice. In doing this he acted in a very excellent and noble way, inasmuch as he had the resurrection in mind; 44 for if he were not expecting the fallen to rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. 45 But if he did this with a view to the splendid reward that awaits those who had gone to rest in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. 46 Thus he made atonement for the dead that they might be absolved from their sin.

The NABRE includes footnote (g):

12:42–45 This is the earliest statement of the doctrine that prayers (v. 42) and sacrifices (v. 43) for the dead are efficacious. Judas probably intended his purification offering to ward off punishment from the living. The author, however, uses the story to demonstrate belief in the resurrection of the just (7:9, 14, 23, 36), and in the possibility of expiation for the sins of otherwise good people who have died. This belief is similar to, but not quite the same as, the Catholic doctrine of purgatory.

Note that the NABRE was a publication of Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Inc., which is an affiliate of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. So, this is not some Protestant take on the subject.

I tend to agree with the point that Judas intended the sacrifice for the living, but that the author (whether that be the epitomizer, the Judeans of Jerusalem, or whomever) has reinterpreted it as beneficial for the dead. The important difference from RC doctrine, however, is that this is to allow the people to achieve the resurrection to life.

Daniel J. Harrington, in his commentary on the NABRE text, First and Second Maccabees, makes much the same point (p. 144):

In the Old Testament context one would assume that Judas and his men were concerned with the collective guilt that might adhere to the living soldiers, and that their prayers and sacrifices were intended to render the surviving soldiers spiritually ready for battle again.

The author of 2 Maccabees, however, gives these actions a different interpretation. In 12:43b-46, he takes as his starting point his firm belief in the resurrection of the dead (see 1 Macc 7) and explains the prayers and sacrifices as having atoning or expiatory value for the dead sinners so that they too might fully participate in the resurrection of the dead. The Catholic practice of prayers for the dead finds some of its Old Testament roots in this author's interpretation of Judas' actions on behalf of his dead soldiers.

Incidentally, the collective guilt interpretation finds further support in the fact that the cost of this sacrifice was shared by the entire group, rather than (for example) by the sale of the possessions of the dead men, or from Judas' personal money. As another aside, I suspect that "1 Macc 7" in Harrington is a typo for 2 Macc 7, as the 2 Maccabees 7:14 refers to the resurrection to life, but there does not seem to be any similar discussion in 1 Macc 7.

*** Update from the same publication day. ***

David Szárász, in a further comment that I hadn't initially seen, added:

I looked up Gallagher´s "The Seventy" and by scholarly consensus 2 Maccabees was written in the 2nd century BC, and let me quote Gallagher here: "2 Maccabees: Palestine; late II BCE"

So even if 12:43-45 is not Jasonic (which I think cannot be conclusively proven), still, 2 Maccabees is pre-Christian.

And the fact that Paul quotes 2 Maccabees chapter 7 (the marytrs) in Hebrew 11:35b (which is acknowledged by scholarly consensus as well), just demonstrates that EVEN if 2 Maccabees chapter 7 would not be Jasonic, it was still an authentic part of 2 Maccabees. It really doesn´t matter whether its Jasonic or not. But as I said, anyone claiming it isn´t, has the burden of proof.

Burdens of proof are not always what they are cracked up to be.

First, I tend to agree with the date of composition that Schwartz offers, which is earlier than the scholarly consensus. His argument that was most persuasive to me was that Nicanor's defeat was only significant until it wasn't significant any more, and that decline in significance happened fairly shortly after the end of what is reported in 2 Maccabees.

Second, there is an important difference between the book as such being pre-Christian and some specific short passage being pre-Christian. In other words, just as "and within three days another will arise without hands" is a Christian interpolation at Mark 13:2, it is not crazy to suggest that there may be Christian interpolations in 2 Maccabees. More on this in a moment.

Third, it is widely thought that the author of Hebrews is referring to the subject matter found in 2 Maccabees 7. Schwartz, for example, at p. 88 writes:

Within the New Testament canon it is generally recognized that the Epistle to the Hebrews shows knowledge of it. For when we read at Hebrews 11:35–36 that “Women received their dead by resurrection (Ἔλαβον γυναῖκες ἐξ ἀναστάσεως), others were tortured on the torture-wheel (ἐτυμπανίσθησαν) … and yet others suffered mocking (ἐμπαιγμῶν) …” it is all but impossible not to see here allusions to 2 Maccabees 6:19, 28 (τὸ τύμπανον) and the story of Chapter 7, including the ἐμπαιγμὸς of 7:7 and the mother’s prayer at 7:29 to receive her children back at the resurrection (7:29); similarly, the reference in Hebrews 11:38, to those forced to take refuge in the deserts and mountains and caves, points straight to our 10:6.

While David Szárász is imprecise in saying "quotes," the underlying idea that there is a cross-reference here is widely accepted.

This, of course, has very little to do with 12:43b-45a, which is not referenced (not alluded to) by the NT or other early Christian writers. Augustine, engaging the Latin version, becomes the earliest example that has been brought to my attention (I'm reluctant to dogmatically insist that it was not mentioned by anyone before that, as his disputant seems to have raised the issue).

I suspect that David Szárász's interest is more in the question of whether Hebrews references 2 Macabees than whether 2 Maccabees 12:43b-45a is pre-Christian.

As to the cross-reference question, the problem is two-fold. First, the story found in 2 Maccabees 6 is also found in 4 Maccabees, and the date of composition of 4 Maccabees is potentially earlier than the date of composition of Hebrews. Thus, if we were to assume that the author of Hebrews was using a source, and were referring to the events described in both books, we could not readily determine which source the author of Hebrews had in mind.

Normally, people focus on the link to 2 Maccabees because 4 Maccabees itself draws from 2 Maccabees. It is not an independent witness to the accounts it describes. So, there is a scholarly preference to show the link back to the earliest source we can identify. Additionally, while the subject matter of chapter 6 is found in 4 Maccabees, the less clear allusions may not have some similar parallel.

That said, if we take 2 Maccabees at face value, 2 Maccabees is itself an epitome of Jason's five-volume work. While scholars have questioned whether that source or another source was used for chapters 6-7, still it is beyond doubt that the author of 2 Maccabees derived the account from another source. We cannot rule out that the author of Hebrews had access to that source directly, rather than mediated by 2 Maccabees or 4 Maccabees (or both).

In short, those seeking to prove that Hebrews was reliant on 2 Maccabees, as distinct from the source or sources of 2 Maccabees, cannot do so. The author of Hebrews does not identify his source.

*** Further Update based on further comments by David Szárász provided by email - I've omitted some courteous pleasantries

David Szárász wrote:

Regarding Schaffer´s comment in the NETS, we need to be careful with statements, which start with „SEEM ALIEN in the context of Jason's history”. Look it might seem alien to him, but since we don´t have Jason´s work, its impossible to tell whether it really wasn´t part of Jason´s work. So at best this is Schaffer´s best guess. Now, with that being said, I don´t have a problem saying that maybe not everything what we have in 2 Maccabees was actually part of Jason´s material. The focus is on 2 Maccabees 12:43-45. So I am not really concerned with the letters or that in some cases we have the epitomator´s added material. We have to focus on the very passage in question. And I would say from what you offered here its impossible to say that this passage wasn´t part of Jason´s work. And in this regard I don´t really see anything compelling from you. You say: “The first level of indent seems to be Jason's original report. It has an essentially neutral tone, and merely reports what happens. The second level of indent seems to attempt to justify/explain the behavior described by Jason.”

Let's turn this sword on its other edge. Given that the epitomizer acknowledges he has altered Jason's text, and given that we have not recovered Jason's original five-volume work, how can anyone prove that something is originally the work of Jason?

Personally, I find the argument that this is a note within a note (and therefore likely not a simple quotation of Jason) to be reasonable. However, I'm very comfortable with letting others disagree about this. No part of my argument regarding Purgatory hangs on this question, nor does any part of my argument against the canonicity of this book hang on this question.

If it could be proven that 12:43b-45a was a post-incarnational edit to the text, it would be a further argument against citation of this passage. However, I think neither side can prove whether this passage was in the text on A.D. 100, given that the earliest copies and versions are apparently centuries later than that and the earliest reference to this passage is likewise centuries later.

David Szárász wrote:

Apart from the fact that you also speculate (you frequently use the word “seems”) there is no single proof that why one should believe that 12:43-45 is a later interpolation. Further what you say: “seems to justify/explain” doesn´t really help. What if the author just simply points out that there is indeed afterlife? This is very plausible since we know there were Jews who denied the afterlife. So the author is aware of contemporary Jews who don´t believe in afterlife, so he gives a rhetoric question? Second thing, you already assume that “resurrection” must mean one single thing. You also assert that this undermines the concept of purgatory, because the sin offering in 12:43-45 helps someone to be resurrected and not to escape purgatory. But again, the point of bringing up the resurrection is not that the sin offering makes the resurrection possible, but rather to simply refute the Jews who deny that there is afterlife. But if there is afterlife, then resurrection here simply can mean that there is life after death while not necessarily denying purgatory. Now one can be resurrected into “life”, i.e. as we say goes to heaven. But resurrection can also have a negative consequence, i.e. one goes to hell. But in this dual system it doesn´t make sense to pray for the dead, because those ending up in hell cannot be brought to heaven and those in heaven don´t need prayers to get there.

Regarding "What if the author just simply points out that there is indeed afterlife?" We know that the author does not just simply point out some generic afterlife, but instead points out the resurrection as such. Furthermore, the author (of the final form of the text) seems to have an eschatology in which only some people are raised, which explains the significance of the resurrection to the author.

2 Maccabees 7:13-14 (NETS)

13 After he too had died, they maltreated and tortured the fourth in the same way. 14When he was near death, he said, “It is desirable that those who die at the hands of human beings should cherish the hope God gives of being raised again by him. But for you there will be no resurrection to life!”

I am curious about David's basis for asserting that the author was aware of "contemporary Jews who don't believe in afterlife." Some scholars have suggested that just as 1 Maccabees is a more Sadducean account, 2 Maccabees is a more Pharisaical account. Others have pushed back against this view. But even if we assume that there were Sadducean or similar Jews at the time, and further that author was aware of their existence, still the author has focused his existence not on the spirit world (that the Sadducees denied, along with the resurrection) but on the bodily resurrection.

David is right that I do think that "resurrection" must mean one single thing, i.e. returning to life, and does not refer to the intermediate state between death and resurrection.

I think it is fair to say that the purpose of the text was not to refute Purgatory (as I don't think that the author had any concept at all of Purgatory), and that it seems likely that it was an attempt to argue for the resurrection.

David Szárász continued:

But let me quote scholars here to illustrate you why you should not assume only one concept under “resurrection” in 2 Maccabees:

“It should be noted, however, that – although our author links the two – belief in post-mortem suffering (and so: Gehenna/Purgatory) need not imply belief in resurrection. One might believe, for example, that those who died are bound to suffer for their sins, and that an appropriate sacrifice might help them out, without any expectation that eventually they will be returned to life; their better future might be a spiritual one. Thus, it seems that for our author the main point here is not resurrection in particular but, rather, the more general thesis that there is some life after death. For a similarly general view of the matter, see Acts 23:8, where various options of life after death are listed and it is said that the Sadducees denied them all. See NOTE on 7:34, children of Heaven, and the bibliography cited there.” (Commentaries on Early Jewish Literature (CEJL), 2 Maccabees by Daniel R. Schwarz, pp. 443-444)

This is from the same commentary by Schwartz that I have been quoting above and agrees with (i.e. confirms) the position that I have been holding. It is at least for this reason that the author of the text cannot have in mind Purgatory as a possibility. It crosses our minds (and Schwartz's) that belief in continued spiritual existence does not have to be linked with a belief in the resurrection, but that option does not occur to the author. It's certainly fine to agree with Schwartz that "the main point here is not resurrection in particular but, rather, the more general thesis that there is some life after death" but the argument that the author uses is, in fact, quite specific to the resurrection and not to other life-after-death regimes.

David Szárász continued his quotations:

“It is sometimes asserted that the resurrection of the body was the characteristic Jewish belief. This is not borne out by the data. A variety of beliefs seem to be attested about the same time in Israelite history. One of these was the resurrection of the body, but there is little reason to think that it was earlier or more characteristic of Jewish thinking than the immortality of the soul or resurrection of the spirit. And it is clear that some Jews still maintained the older belief in no afterlife.” (An introduction to Second Temple Judaism, Lester Grabbe, P. 93)

“The exact form of the resurrection is not always specified, but we should not expect it always to entail resurrection of the body. Sometimes only the resurrection of the spirit is in mind, as in Jubilees 23:20–22 “(p. 94)

“Some believed in a resurrection of some sort, though there was not unanimity even on this point: some conceived of it in terms of a resurrection of the body, some as resurrection of the spirit, and often no details were given at all. Others believed in the immortality of the soul without any reference to a resur- rection. Finally, a number of sources seem to combine belief in the immortal soul with a resurrection of some sort.” (p. 106)

“Some texts envisage a resurrection, but even this takes more than one form. Some think of a restoration of the original physical person to life, but others clearly think of a ‘resurrection of the spirit’. “(p. 136)

Keep in mind that Grabbe is aiming to describe the views of Jews from roughly 500 BC to AD 70. So, in these broad conceptions, he's discussing the views of many different authors and sects of the Jews. When discussing the bodily resurrection view, the first non-canonical source that Grabbe cites is 2 Maccabees (pp. 93-94):

Apart from Isaiah 24-27 which is difficult to date, the earliest datable reference to the resurrection is Daniel 12:2 from about 165 BCE. Here the resurrection is not universal but involves only some of the dead. The righteous achieve what is referred to as ‘astral immortality’; that is, they become like the stars of heaven (12:3). After this resurrection is found widely in the literature.

A good example is 2 Maccabees 7 which describes the torture and death of a mother and her seven sons because they refused to break the law:

[7:9] And when he was at his last breath, he said, ‘You accursed wretch, you dismiss us from the present life, but the King of the universe will raise us up to an everlasting renewal of life, because we have died for his laws.' After him, the third was the victim of their sport. When it was demanded, he quickly put out his tongue and courageously stretched forth his hands [to be cut off], and said nobly, ‘I got these from Heaven, and because of his laws I disdain them, and from him I hope to get them back again.’

This seems to expect the resurrection of the body, because the parts cut off would be restored.

I don't endorse everything Grabbe says here or elsewhere. For example, I find his dating of Daniel (while consistent with unbelieving scholarship) to be far too late, and similarly his dating of Isaiah far too skeptical.

There are other things where I would tend to agree with Grabbe, such as when he observes regarding events after Antiochus' attack on Jerusalem: "Events from then on become somewhat uncertain because the data given in 1 and 2 Maccabees do not always make sense." (p. 15) Likewise, from early on the same page: "Antiochus accomplished all his goals and returned in triumph with a great many spoils. Although the accounts in both 1 and 2 Maccabees are plainly confused, it seems that it was while on his way back from Egypt that he visited Jerusalem, was taken into the temple itself by Menelaus (in violation of the law), and raided the temple treasury to the tune of 1800 talents." (p. 15)

Elsewhere, Grabbe's personal bias against the supernatural shines through. While I share his disbelief about the veracity of the account, I do so for somewhat different reasons (pp. 9-10):

A strange episode took place under Seleucus, if there is any truth in 2 Maccabees 3. Seleucus was informed that a good deal of money was kept in the Jerusalem temple treasury, so he sent one of his officers to confiscate it for the royal coffers. This seems not to have happened, though. According to 2 Maccabees, this was because of a miracle in which an angel of God suddenly intervened. Exactly what happened is unclear, since few of us are willing to take the account of 2 Maccabees at face value. Why would Seleucus attempt to seize the temple money? One of the reasons seems to be that a large deposit of Hyrcanus Tobiad's was being kept there (2 Maccabees 3:11) and, as noted above, Hyrcanus was probably pro-Ptolemy and thus regarded as an enemy of the state by Seleucus. Why Seleucus' minister failed to take the money remains a matter of speculation, assuming that the story is not sheer legend.

David Szárász concluded:

So as you can see “resurrection to life” as in 2 Maccabees 7:14, only means that these martyrs will go straight to heaven. There is no need to pray for them. But some will be resurrected to Gehenna (i.e. no resurrection TO LIFE). And some need prayers, those who sinned and cannot go directly to heaven.

No. As explained by Grabbe (and as deducible from 2 Maccabees 7), the resurrection to life envisioned by the author of the final form of 2 Maccabees is a bodily resurrection, otherwise the character offering his tongue and hands to be cut off would have no expectation of receiving them again.

Recall as well that many people think that the story recounted in 2 Maccabees 7 is the one that the inspired author of Hebrews alludes to in Hebrews 11:35 (KJV) "Women received their dead raised to life again: and others were tortured, not accepting deliverance; that they might obtain a better resurrection:" (whether 2 Maccabees 7 or Jason's work or another source of the author of 2 Maccabees is the source for the author of Hebrews is an interesting tangent that I won't explore here).

Indeed, not only the fingers/tongue portion but also the mother's own exclamation affirms that a bodily resurrection (not mere transit from one spirit realm to another) is in view:

2 Maccabees 7:20-23 (NETS)

20 The mother was especially admirable and worthy of honorable memory. Although she saw her seven sons perish within the course of a single day, she bore it with good courage because of her hope in the Lord. 21She encouraged each of them in their ancestral language. Filled with a noble spirit, she reinforced her woman’s reasoning with a man’s courage and said to them, 22“I do not know how you came into being in my womb. It was not I who gave you life and breath, nor I who set in order the elements within each of you. 23Therefore the Creator of the world, who shaped the origin of man and devised the origin of all things, will in his mercy give life and breath back to you again, since you now forget yourselves for the sake of his laws.”

David Szárász concluded:

So your claim that “According to 2 Maccabees 7:14, the resurrection to life is not for everyone. Thus, the motive for the sin offering is to make sure that the idolatrous soldiers can join in the resurrection to life. However, under the Roman Catholic conception of Purgatory, everyone who is in Purgatory is already guaranteed participation in the resurrection to life.” is a misreading of 2 Maccabees and wrong comparison with the concept of Purgatory. 7:14 does only say that the martyrs will be resurrected TO LIFE and those others won´t be resurrected TO LIFE. The point isn´t that only some will be resurrected, the point is that only some will be resurrected TO LIFE. However, everybody will be resurrected, but only some TO LIFE, and some to eternal torment. “Life” here means heaven, just as John 3:15 says “that everyone who believes in Him may have eternal life.” Clearly, we both agree that also who don´t believe in Jesus will have eternal life, but life in John 3:15 means heaven. So the same thing as in 2 Maccabees. But in 12:43-45 sin offerings are warranted to help to achieve resurrection, i.e. they need prayers to be resurrected TO LIFE – i.e. get to heaven. But from where? Well, purgatory is the only reasonable answer.

On the contrary, attempting to spiritualize "resurrection to life" into something other than the bodily resurrection is the mistake. I should point out that the even the footnotes of the USCCB's publication of 2 Maccabees, at 7:9 (link) confirm my point (as well as that of Grabbe and Schwartz):

* [7:9] The King of the universe will raise us up: here, and in vv. 11, 14, 23, 29, 36, belief in the future resurrection of the body, at least for the just, is clearly stated; cf. also 12:44; 14:46; Dn 12:2.

I set aside here our divergent interpretations of John 3:15, to minimize the number of rabbit trails for us to explore.

In summary, the only reasonable interpretation of "resurrection" is actual resurrection. That's not to suggest that the polemical point is only about actual resurrection, but to deny that it is explicitly about the actual bodily resurrection is something that I have not seen from any of the various commentators I've surveyed. In this error, Szárász seems to be alone, although I certainly lack omniscience of all the interpreters out there.

David Szárász continued:

Your speculation that in 2 Maccabees 12, that the sin offering was made “to remove corporate guilt” could be interpreted only if we ignore 12:43-45. But that is the question at hand, why should we ignore it? You speculate that it might be a later Christian interpolation. Ok, such claims can be made, but again, what is the evidence? To me there is ZERO data that support this claim. All you did is you offered the FN from NETS (C. Habicht, 2. Makkabäerbuch). Well I tell you this, I looked into that and he offers zero evidence as well (If you want I send it to you via email). And if this is the case, I don´t see any reason why one would say that 2 Maccabees doesn´t teach purgatory, when it indeed does. 12:43-45 clearly states that the sin offering was made for those who died and that so they can be loosen from their sin. This is the concept of purgatory.

No. It's not necessary to ignore 43-45 to reach that conclusion. All that is necessary is to understand that the structure of the text is something like this (NETS text):

He also took up a collection, man by man, to the amount of two thousand drachmas of silver, and sent it to Hierosolyma to provide for a sin offering.

In doing this he acted very well and honorably, taking account of the resurrection. For if he were not expecting that those who had fallen would rise again, it would have been superfluous and foolish to pray for the dead. But if he was looking to the splendid reward that is laid up for those who fall asleep in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought.

Therefore he made atonement for the dead so that they might be delivered from their sin.

The first level of indent is reporting what happened. The second level of indent is the commentary on that action. When considered outside the parenthetical, the "they might be delivered" in the final portion is (in itself) ambiguous between the dead soldiers and the living soldiers.

Admittedly, it's not perfectly clear whether the "therefore" is part of the preceding parenthetical commentary or a continuation of it. If I'm mistaken and it's a continuation of the preceding parenthetical, it's not part of the report of what Judas did, but rather a commentary on what Judas did.

If it's a report of what Judas did (and therefore not part of the parenthetical commentary), then it's ambiguous as to whether Judas expected the living or the dead to benefit from atonement for the sins of the dead people. Considering that Judas had the men themselves pay for this sacrifice, the implication is that the men are the expected and intended beneficiaries.

This, of course, clashes with the parenthetical commentary at 43b-45a. However, we don't have ignore that commentary, just disagree with it. In other words, we can (and I do) think that the author of 43b-45a misunderstood and misinterpreted Judas' actions.

On the other hand, even the author of 43b-45a did not have in mind Purgatory, for reasons that I've already explained above. So, even if the author of 43b-45a was right in thinking that Judas intended to try to expiate the sins of the dead on behalf of the dead, still the passage undermines the RC dogma of purgatory, because the author's argument assumes that the only reason to pray for the dead is so that they can participate in the bodily resurrection of the just.

David Szárász continued:

I appreciate all the work you put into and the scholars you cite, but many of these scholars actually only demonstrate how there is much disagreement whether 12:43-45 is indeed an interpolation. I always say, if we don´t have sufficient data, we cannot simply assume that this is an interpolation. So for example you cite Doran, but Doran says also “This section has been the subject of much discussion” . I.e. there is no scholarly consensus. And if there is no scholarly consensus, why should anyone take it as granted?

People should be persuaded by evidence and sound arguments, whether or not there is consensus. If I were trying to persuade folks to accept the idea that this is definitely an interpolation, I would offer the evidence and sound arguments that I hope would persuade them.

David Szárász continued:

Regarding the “corruption” of the Latin translation. Honestly, I don´t care about that much. You argue that v 45 in Greek does not include the word “pray”. But how is that even relevant? Its right there in the previous verse (v44) - ὑπὲρ νεκρῶν προσεύχεσθαι – “pray for the dead”. So even if I would just stick with the Greek, it still teaches praying for the dead to loose them from sin, i.e. Purgatory.

Focusing on the author of 43b-45a, in the Greek that author does not endorse the action of praying for the dead, just the intention of looking toward the resurrection. The author feels that the action itself is an odd one, in need of explanation, and he finds a way to praise Judas for having his mind on the resurrection. Describing that Judas prayed for the dead (as per the author of 43b-45a) is different from endorsing prayer for the dead (as per the Latin gloss at Latin vs. 46). It may seem like a subtle difference, but it is an important difference.

David Szárász continued:

Now let’s go to 7 Maccabees. You say I am wrongly stating that it is “quoted” in Hebrews 11. First of all, all the people that are mentioned in Hebrews 11 are exclusively OT figures. And no one doubts that the author here includes the martyrs from 2 Maccabees. Many many scholars affirm that the author of Hebrews is describing people exclusively from the Sacred Scriptures – i.e. Old Testament, I would say this is a consensus among scholars. And I don´t really now of ANY scholar who denies this. For an in depth treatment of this watch Gary´s video: [link inserted here by T-Fan]

There is a lot of hand-waving here. There are Protestant scholars who deny that 2 Maccabees is part of Sacred Scriptures and who yet see a reference to the martyrs described in the story reported in 2 Maccabees 7. So, it's certainly not the case that there is a "consensus among scholars" on the idea that the author of Hebrews is describing people exclusively from the Sacred Scriptures.

Likewise, while many scholars see the "sawn asunder" as a reference to the death of the prophet Isaiah, they don't suggest that the account of the death of the prophet Isaiah is itself canonical.

All of the scholars should agree that people the author of Hebrews has in mind are those before the incarnation (see vss. 39-40), but there is nothing in the text to tell us that the author has in mind exclusively canonical accounts of people or even only people mentioned in canonical scripture.

David Szárász continued:

Now you mentioned it might be referencing 4 Maccabees. There are several reasons why this is not plausible. One of them is that AT BEST the book was written late 1st century and in a completely different area, not in Palestine (contrary to 2 Maccabees) as Gallagher sums up: 4 Maccabees: Alexandria? Antioch? Asia Minor?; late I CE (source: The Translation of the Seventy). So even if its lets say contemporary to the author of Hebrews, there is not enough time for this book to get disseminated and widespread from the area it was written, much less would it gain such authority. But there are also scholars who argue for a 2nd century AD date, so that makes it outright impossible to be quoted in Hebrews. Second, the theme in 4 Maccabees is entirely different, it’s a more a philosophical work and the martyrs mostly emphasize that they refuse eating defiled food, because they respect the Law, they respect the ancient faith and because out of commitment to God. However resurrection is not the reason at all. Sometime it mentions the afterlife, but the emphasize is on piety and commitment to the Law. While when you read 2 Maccabees resurrection is right there and explicitly. So 4 Maccabees does not really fulfill the third criterion from Hebrews (“for a better resurrection”), while 2 Maccabees does. Just read 4 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees, you will notice the difference, but Gary mentions this in his video as well with scholarly support. Further you said the fact that Hebrews use 2 Maccabees doesn´t prove anything about 12:43-45. That is true, but usually the claim is that these non-Jasonic passages are the interpolations of the epitomator, i.e. chapt. 7 and 12:43-45 are the interpolations of the same person (epitomator) then the fact that Paul knows about chapt 7, then he must be familiar also with 12:43-45. Now you can claim that 12:43-45 could be added even later than chapt. 7. Look, as I said, we can make all kinds of claims and everything is possible, but what is the warrant for this claim? I just don´t see that anywhere.

Some of the estimates for the dating of 4 Maccabees are earlier than that. David deSilva in his introduction (p. xiv) on 4 Maccabees (Brill, 2006) explains:

Modern scholars agree that 4 Maccabees was composed sometime between the turn of the era and the early second century C.E. For a work that is attached to no known author, connected with no known location, tied to no particular occasion, and devoid of references to contemporary events, one might look in vain for greater specificity than that.

deSilva goes on to consider the various evidence and arguments and favors the "later part of the proposed range of 19-72 C.E." as the date of composition. The dating of Hebrews is itself somewhat hotly contested, but to suggest that it's out of the question that 4 Maccabees was composed first is unreasonable.

As for the place of composition, deSilva argues that as compared to Alexandria, "Stronger evidence points north and west of Palestine to the area between Syria and Asia Minor as a more probable region of origin. Syrian Antioch, which also hosted a large Jewish community, has been a favorite choice of more recent scholarship...." (p. xviii) Antioch is famously a place with strong early Christian ties as well, and consequently it would not require a theory of widespread dispersal to account for the author of Hebrews to have access to the work.

There is no need for the book to gain authority in order to serve as a literary source. After all, as mentioned above, the martyrdom of Isaiah (the usual explanation for the "sawn asunder" phrase) is not from a work of any known authority.

I agree that 4 Maccabees 1 (NRSV updated edition) explains: "The subject that I am about to discuss is most philosophical, that is, whether pious reason is sovereign over the passions."

It is interesting to note that the story as told in 4 Maccabees does not seem to include any explicit mention of the resurrection. Still, the story is the same and the characters are the same characters.

The interpretation of the source text is characteristic of Hebrews 11. For example, "Esteeming the reproach of Christ greater riches than the treasures in Egypt: for he had respect unto the recompence of the reward." in verse 26 is an interpretation, not a quotation, of the Exodus account of Moses. It is a true and right interpretation, of course. So, it is not a stretch for the author of Hebrews to give the resurrection interpretation to the mother's actions.

Moreover, deSilva argues that 4 Maccabees is influential in some New Testament writings (p. xxxii): "In regard to Hebrews and the Pastoral Epistles, a stronger case for actual influence, rather than merely points of contact, can be made ...." deSilva seems to agree that 2 Maccabees rather than 4 Maccabees is in mind because of the explicit reference to resurrection (see p. xxxiii) and he goes on seemingly to acknowledge that "the stamp of 4 Maccabees upon the New Testament is debatable..." (p. xxxiv).

So, I'm going slightly beyond deSilva to suggest that 4 Maccabees is a valid candidate for the source. 2 Maccabees is a more natural suggestion given its composition prior to 4 Maccabees and its inclusion of explicit references to the resurrection.

Keep in mind that we have yet another potential source for the story, namely the same source as the author of the final form of 2 Maccabees. The author of 2 Maccabees does not deny that he used sources (i.e. at least the five books of Jason), and while we do not have those sources, it's not unreasonable to think that the author of Hebrews could have had access to those sources.

So, even if deSilva's dating of 4 Maccabees before Hebrews (and influence on Hebrews) is wrong (and it may be), it does not prove that the source of the martyrs story for the author of Hebrews is 2 Maccabees.

If we assume that the author of Hebrews did rely on 2 Maccabees for the story of the martyrs, it would be reasonable to suppose that the author of Hebrews had a form of 2 Maccabees that included Judas offering a sacrifice after the death of his soldiers. The simplest theory is that the same editor who included resurrection in 2 Maccabees 7 also included it in 2 Maccabees 12. So, that would imply that the author of Hebrews probably would have seen that passage as well (on the assumption that he had read that book). Clearly we are deep in speculation at this point. Nevertheless, if we are going to make those assumptions, we should also assume that the author's unambiguous statements that the work is his own effort (See the "source issues" section above), and consequently would not have regarded it as being some kind of work of divine inspiration.

David Szárász continued:

Now its intriguing how you cite scholars in your article how 2 Maccabees was not really read by the Jews. That is interesting because 4 Maccabees is a Jewish work and it is a retelling of 2 Maccabees from a philosophical perspective. Jews held these martyrs in great esteem, the reason why it might fell out later in rabbinic circles could be political. But for the author of 4 Maccabees these were just as great people as Abraham, Isac, Jacob, etc. For instance this is what is written by the author of 4 Maccabees in 1:10: “On the anniversary of these events it is fitting for me to praise for their virtues those who, with their mother, died for the sake of nobility and goodness, and I would also call them BLESSED for the honor in which THEY ARE HELD.”

As Schwartz explains (p. 86):

Nevertheless, until the late first century C.E. (at the earliest) we know for sure of only one Jewish reader of our book: the author of 4 Maccabees, who retells at length the martyrdom stories of 2 Maccabees and also includes a version of the Heliodorus story. Philological comparison leaves virtually no room for doubt about its use of our book.

In a footnote that seems relevant to our discussions, Schwartz acknowledges that the glosses introduced into the text and present in most witnesses suggests that the book had use at an early time (p. 86):

[FN 196] So too, we may note that here and there it seems that glosses have been introduced into the text; see above, p. 37, n. 80. The fact that they are attested to by many or all of the witnesses points to their antiquity.

Of course, if someone is claiming that the glosses are actually original, one cannot avail themselves of this evidence of usage.

As for "fall out later," it hasn't been established that it had significant early acceptance in Judea. It was written in Greek. Even if assume that some group of Jerusalemite Judeans originally composed the final form to promote the already-existing feast of Hanukkah (the usual assumption), it does not seem that it was widely embraced.

I certainly agree that the author of 4 Maccabees held the martyrs in high esteem. Of course, there is a huge difference between holding the martyrs in high regard and holding the book as Scripture. We may admire the heroism of Jan Žižka or Charles Martel without ascribing their biographies with any special authority. Foxe's Book of Martyrs may be inspiring, but it is not inspired. Jerome's Of Illustrious Men is worthwhile read, but it is not infallible.

David Szárász continued:

So clearly the author claims that the Jews really admire these people and commemorate them, he says he writes these things since its their anniversary. And I could go on and on how the author praises Eleazar, the 7 brothers and their mother. Its incredible.

The story of their martyrdom was known before the composition of 2 Maccabees as well and (we assume) was included by the epitomizer because of how it compelling it is. That author also praises them. It's not unreasonable to assume that the story of Eleazar and the seven brothers and their mother (found in a somewhat different form in the Babylonian Talmud) was popular among the Jewish diaspora. It's short enough to be committed to memory (cf. 2 Maccabees 2:25, which suggests memorization of the story) and to be transmitted orally. Both that story and the salvation of the treasury story are found in 4 Maccabees.

David Szárász continued:

Now the bottom line. To me its really irrelevant whether 12:43-45 is Jasonic or not, but I really don´t see anything in the data that proves that it isn´t. And even if I would agree it is not Jasonic, to me it is irrelevant, for me what is important is that 2 Maccabees is the inspired work, not Jason´s. Further I don´t see any good reason to believe that 12:43-45 would be an interpolation by a Christian. I just don´t see anything, nor do I see this in any of the scholars you cited. But If I missed something, please correct me.

What proves it to one person might not to another. Nevertheless, no one claims that Jason was inspired. So, in some ways it seems worse for those trying to build doctrine on 2 Maccabees to say that the author is merely quoting Jason here. Again, though, this issue is not at all central to my arguments regarding 2 Maccabees 12 and Purgatory.

Belief in the resurrection is arguably the central claim of Christianity. Moreover, 4 Maccabees (presumably by a Jewish diaspora author) apparently draws from 2 Maccabees but avoids reference to the resurrection that is found in the story in its current form in 2 Maccabees. I think this falls far short of proof of Christian editing of the text, but it does not make such editing wholly impossible.

David Szárász continued:

But here is the thing. If really this is something that is so important for you then I would expect you to be consistent in what the scholars say, especially the scholarly consensus. For instance, the book of Ezra, as we have it, was clearly heavily interpolated. In some passages Ezra speaks in the first person, sometimes he is mentioned in the 3rd person. Moreover part of Ezra was written in Hebrew, part in Aramaic. Clearly Ezra would not do any of these things, that just doesn´t make sense. So scholarly unanimously agree that the original work – Memoirs of Ezra – later developed and just much much later became the book as we know it. This fact is quite damaging for anybody who believes in the 400 years of silence during the so called intertestamental period, because this means the book of Ezra is contaminated with multiple uninspired passages. But I could go on with other books as well, like proto-, deuteron- and tritto- Isaiah. Or the book of Daniel is generally considered to be a 2nd century work, or at least its latest redaction. Scholars even say that Daniel´s prophecy fails in regards to the circumstances of the death of Aniochus Epiphanes. We even have manuscript evidence, how the book of Jeremiah developed. In the dead see scrolls, the shorter version 4Q70 is dated to the late 3rd century BCE, while the expanded version 4Q72b is dated to the 2nd century BCE. In fact, the LXX version is much shorter than the Masoretic. Clearly the data shows not all of Jeremiah was written by Jeremiah. These are much more clearer evidence for later interpolations than the speculations around 2 Maccabees. So how are you going to be consistent in these instances?

Today (October 2), I heard part of an episode David Szárász did with William Albrecht and Gary Michuta, in which he raised some of these same kind of objections. It feels a bit like a Tu Quoque fallacy, but these are points that deserve answers. And evangelical scholars have offered answers, either refuting the claims (in the case of deutero- etc. Isaiah) or simply rejecting the later interpolations (e.g. the additions to Esther have been rejected by Protestants).

There are much more significant objections to the alleged canonicity of 2 Maccabees than the possibility of subsequent tampering with the text by Christians. I think a few have been mentioned above, and more could be added, but as that's not the focus of this response, I'll set that to the side.

*** Further Update