The anonymous author of the KJV Today is not, I assume, any of the other authors I've already responded to when it comes to Revelation 16:5. This author has an article on Revelation 16:5 (link to article). The article was titled "Beza and Revelation 16:5." I have tried to preserve the substance of the article, but I have changed the format, added some section numbering for convenient reference, removed formatting.

In some ways, the KJV Today article seems to be a clearinghouse for a lot of the material I've already addressed in Nick's book (see this 20+ video series), as well as other material I've addressed from other authors, such as Edward G. Hills, Thomas Holland, and Jeffrey Khoo. I will refer to the author of the KJV Today article as "KTA," short for KJV Today Author.

I. Response to "Introduction"

Under the topic, "Introduction," KTA provides six sub-sections, which I've designated, respectively, as 1.1 through 1.6. I'll respond to each in turn.

1.1 Revelation 16:5 in the KJV

"Which wert and art, and evermore shalt be!" - This epic line from the famous hymn by Reginald Heber (1783-1826) comes from Revelation 16:5 in the KJV. Revelation 16:5 in the KJV says:

"And I heard the angel of the waters say, Thou art righteous, O Lord, which art, and wast, and shalt be, because thou hast judged thus."

This KJV reading is based on Theodore Beza's 1598 edition of the Textus Receptus. Critics, however, raise issue with the reading "and shalt be" (και ο εσομενος) because it does not appear in any existing manuscript. Existing manuscripts read "holy one" (και οσιος), "that holy one" (ο οσιος) or "and holy one" (και οσιος). For example, Revelation 16:5 in the Nestle-Aland 26 based NASB Update reads:

"And I heard the angel of the waters saying, "Righteous are You, who are and who were, O Holy One, because You judged these things;"

Since there is no existing manuscript with Beza's reading, critics dismiss Beza's reading as an unwarranted conjectural emendation. However, an in-depth study of the issue will reveal enough evidence to validate Beza's conjectural emendation.

Reginald Heber's hymn, "Holy, Holy, Holy," is actually based on Revelation 4:6-11. We can see this from the language "Holy Holy Holy" drawn from Revelation 4:8, from the ordering of the past tense "wert" before the present tense "art," which is distinctive of 4:8, from the "casting down their golden crowns," which is from 4:10, from the "glassy sea" which is from 4:6, from "all thy works" based on 4:11 and from "evermore shall be" from 4:10. I would be tempted to see "only Thou art holy" as an allusion to Revelation 16:5 (which calls Jesus "O Holy One"), but most likely it is simply drawn from 4:8, or perhaps illuminated by Revelation 15:4, which states "Thou only art holy." The latter passage also makes reference to the glassy sea at 15:2 and makes more specific reference to angels at 15:6 as well as mentioning the creation as God's works at 15:3 and describing all nations as coming to worship him at 15:4. It also gives a sense of darkness at 15:8, which similarly connects to the Old Testament text on which Revelation 4:8 is based, namely Isaiah 6:3-4. So, sadly, KTA is off on a wrong foot from the start.

The KJV translators certainly did translate Revelation 16:5, which in their Greek text had "και ο εσομενος" with "and shalt be." That, however, is not a strictly literal translation of the Greek. A strictly literal reading would be "and the Will-Being One" or "the one who is to be." The KJV translation is, however, a fairly literal translation of Beza's Latin, "et qui eris," ("and [thou] who shalt be"). It probably makes sense to see the KJV translators as following not only Beza's textual decision here, but also his translational methodological decision as well.

Regarding, "Existing manuscripts read "holy one" (και οσιος), "that holy one" (ο οσιος) or "and holy one" (και οσιος)," KTA seems to have some mistaken understanding, which we can clarify. The Greek manuscripts have (among other readings):

- ο οσιος ("O Holy One") (this is the correct and most frequent reading)

- και οσιος ("and Holy")

- και ο οσιος ("and the Holy" or "and O Holy One")

The third reading seems to include an extraneous article, which caught Beza's attention as a grammarian. Unfortunately, his correction to the Greek text was wrong. He did not consider the possibility that Jesus was being called "O Holy One" here.

I note that KTA calls it a conjectural emendation, in agreement with Hills and Holland. I think KTA is basically correct about this, although I do not think that Beza realized it was a conjecture when he incorporated it into his text. More about that below.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:1.2 Beza's Conjectural Emendation

Beza gave the following explanation for his conjectural emendation in the footnote to Revelation 16:5:

Click the image to enlarge the original Latin footnoteEnglish translation:

"Et Qui eris, και ο εσομενος": The usual publication is "και ο οσιος," which shows a division, contrary to the whole phrase which is foolish, distorting what is put forth in scripture. The Vulgate, however, whether it is articulately correct or not, is not proper in making the change to "οσιος, Sanctus," since a section (of the text) has worn away the part after "και," which would be absolutely necessary in connecting "δικαιος" and "οσιος." But with John there remains a completeness where the name of Jehovah (the Lord) is used, just as we have said before, 1:4; he always uses the three closely together, therefore it is certainly "και ο εσομενος," for why would he pass over it in this place? And so without doubting the genuine writing in this ancient manuscript, I faithfully restored in the good book what was certainly there, "ο εσομενος." So why not truthfully, with good reason, write "ο ερχομενος" as before in four other places, namely 1:4 and 8; likewise in 4:3 and 11:17, because the point is the just Christ shall come away from there and bring them into being: in this way he will in fact appear sitting in judgment and exercising his just and eternal decrees. (Theodore Beza, Novum Sive Novum Foedus Iesu Christi, 1589. Translated into English from the Latin footnote.)

Although Beza is silent, he could have been influenced in making his change based on a minority Latin textual variant. There are two Latin commentaries with readings of Revelation 16:5 which agree with Beza in referring to the future aspect of God.

First, this is a poor and misleading translation of Beza's annotations at Revelation 16:5. The following is a better translation:

5 And who [you] will be, καὶ Ό ἐσόμενος. It is commonly read, καὶ ὁ ὅσιος, the article indicating, against all manner of speaking, that the scripture has been corrupted. But whether the Vulgate reads the article or not, it translates ὅσιος no more correctly as "Sanctus" (Holy), wrongly omitting the particle καὶ, which is absolutely necessary to connect δίκαιος (righteous) & ὅσιος. But when John, in all the other places where he explains the name of Jehovah, as we said above, I.4, usually adds the third, namely καὶ Ό ἐρχόμενος, why would he have omitted that here? Therefore, I cannot doubt that the genuine scripture is what I have restored from an old bona fide manuscript (lit. old manuscript of good faith), namely Ό ἐσόμενος. The reason why Ό ἐρχόμενος is not written here, as in the four places above, namely I.4 & 8, likewise 4.8 & 11.17, is this: because there it deals with Christ as the judge who is to come; but in this vision, He is presented as already sitting on the tribunal, and exercising the decreed judgments, and indeed eternal ones.

Simply comparing the two translations, you can see that the differ in important respects.

Second, while KTA (or KTA's source) may have obtained the image/translation from a 1589 printing, this annotation was first published by Beza in 1582. I don't mention this as an error, so much as being an opportunity to be more precise.

Third, there is no reason at all to suppose that Beza was influenced by Beatus' commentary, because Beza himself does not mention that he was influenced by Beatus' commentary. Moreover, Beatus' commentary, while presenting a different Latin translation from the Vulgate, does not correspond to Beza's Greek, because it has two verb tenses and "holy" not three verb tenses. The Old Latin translation apparently used by Tyconius and from thence apparently copied by Beatus does use a future tense verb in translation. Beza also uses a future tense verb in translating from Greek to Latin. However, as mentioned above, Beza uses three verbs in his translation, whereas Beatus/Tyconius' translator used only two verbs, and maintained "holy." So, the agreement is quite limited. For someone with Beza's skill in languages, it would not have provided support for his substitution.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

1.3 Beautus: "Futurus Es"

Beatus of Liebana, a Spanish theologian from the 8th century, wrote a commentary on the book of Revelation titled, "Commentaria In Apocalypsin". A copy of it is available as a Google Book. The date of Beatus' readings may go as far back as 360 AD as Beautus relied on Tyconius' materials. The following is Beatus' excerpt of Revelation 16:5:

Beatus' text reads, "Justus es, qui fuisti, & futurus es Sanctus" (Just are you, which hast been and wilt be the Holy One). This reading is not exactly the same as Beza's, but as in Beza's reading the future aspect is included in the address to God.

As mentioned above, this translation does not support Beza's substitution change to the Greek text. The best explanation for the odd Old Latin translation is that "has been and will be" is intended to convey the sense of ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν ὁ ὅσιος based on an understanding that this phrase is intended to convey God's quality of eternally being Holy. As such, it simply is another confirmation of the most frequent reading found in the extant Greek manuscripts.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

1.4 Haimo: "Es & Eris"

Haimo Halberstadensis, a German bishop in the 9th century, wrote a commentary on the book of Revelation, also titled, "Commentaria in Apocalypsin". A copy of it is available as a Google Book. The following is the commentary portion of Revelation 16:5:

The text from "dicentem" to "eris" translated into English is:

"[Saying: Thou art just, who were holy.] In past times it is used here for three times, that is, for the past, present, and future. Who were holy, are and shall be just."

There are two interesting features of this commentary. First, the quotation from the biblical text, [dicentem: Justus es qui eras sanctus.] is not Beza's conjectured reading. However, it is neither the reading found in the existing manuscripts nor in the Vulgate. The reading, being translated, "You are just, who were holy" is missing the clause, "and who are" (Latin: "& qui es"). The Vulgate reads, "dicentem iustus es qui es et qui eras sanctus".

Second, the commentary includes the sentence, "Who were holy, are and shall be just", using the verbs, "eras", "es" and "eris". The association of "justice" with the past, present and future only occurs at Beza's Revelation 16:5. The previous triadic declarations at 1:4, 1:8, 4:8 and 11:17 do not associate the formula with God's "justice". Haimo's commentary text carries the sense of Beza's Latin translation of his 1598 Greek Textus Receptus, which reads, "Justus es, Domine, Qui es, & Qui eras, & Qui eris". Beza chose "eris" as the translation of "εσομενος" (shalt be), which is also the Latin word in Haimo's commentary. Haimo used "eris" (shalt be) for the future rather than "venturus est" (is to come) despite the previous occurrences of the formula in Revelation 1:4, 1:8 and 4:8 in the Vulgate having "venturus est" as the future.

It appears as though the original commentary included the biblical text as conjectured by Beza, and whoever compiled the present edition of the commentary took the commentary section from the original commentary and took the biblical text from a faulty version of the Vulgate.

First, the commentary on the Apocalypse is misattributed to Haimo of Halberstadt. It should, instead be attributed to Haimo of Auxerre, with a date of approximately A.D. 855 (see here). For our purposes, that doesn't make much of a difference.

Second, it is important to have an accurate translation of the text of Haimo of Auxerre, aka Ps.-Haimo of Halberstadt. In the interest of providing the full context, I offer the entire discussion of Revelation 16:5.

PL 117, 1128D-1129C, has the following text for Ps.-Haimo of Halberstadt (link to source):

Transcription:

Et audivi angelum aquarum. Id est, nuntium populorum, quia, sient in sequentibus legimus, aquæ multæ populi multi sunt. Dicentem: Justus es qui eras sanctus. Præteritum tempus positum est hic pro tribus temporibus, id est, pro præterito præsenti et futuro. Qui eras sanctus, justus es et eris. Quæ justitia in hoc manifestatur, cum subditur: qui hæc, inquit judicasti quia sanguinem sanctorum et prophetarum effuderunt et sanguinem eis dedisti bibere. Justum enim est apud te, ut quia sanguinem sanctorum tuorum effuderunt, ipsi sanguinem bibant. Hoc est vindictam effusi sanguinis sustineant, et in tui cognitionem minime perveniant hi qui, bona sibi annuntiantes, non solum non audierunt, verum etiam crudeliter peremerunt. Quod intelligendum est tam de Judæis quam de gentibus. Judæi enim fuderunt sanguinem sanctorum prophetarum sicut interfecerunt Ezechielem, et Isaiam secuerunt, Jeremiam lapidaverunt. Unde et Stephanus eis in contentione, quam cum illis habuit improperat, dicens: Quem prophetarum non sunt persecuti patres vestri? Et occiderunt eos qui prænuntiabant de adventu justi. Gentiles quoque similiter multum sanctorum martyrum sanguinem fuderunt, sicut Nero crucifixit Petrum, decollavit Paulum et multos alios. Hi omnes justo Dei judicio postea biberunt sanguinem, id est, vindictam sanguinis pertulerunt: vel in præsenti, sicut Judæi et ipse Nero, ut perderent et præsentem vitam et futuram: vel in inferno damnati, et perpetuis cruciatibus traditi. Unde Dominus in Evangelio dicit: Requiretur sanguis omnium sanctorum a generatione hac reproborum, qui effusus est super terram a sanguine Abel justi, usque ad sanguinem Zachariæ. Aliter: Sanguis sanctorum prophetarum intelligitur spiritualis sensus illorum. Qui igitur sanguinem prophetarum vel cæterorum sanctorum fuderit, id est, qui spiritualem illorum sensum in terrenum intellectum converterit, sanguinem bibet, id est, vindictam sanguinis sustinebit. Hoc est, quidquid vitale habere videtur, perdet, et in carnali sensu remanebit justo Dei judicio. Digni enim sunt. Dignum est enim, ut is qui spirituale vinum bibere noluit, corruptionibus vitiorum tanquam sanguinibus debrietur.

The English translation of the above is this:

And I heard the angel of the waters. That is, the messenger of the peoples, because, as we read in the following, many waters are many peoples. Saying: You are just, who were holy. The past tense is placed here for three times, that is, for past, present, and future. Who were holy, you are just and will be. This justice is manifested when it is added: for these, he says, you judged because they poured out the blood of the saints and prophets and you gave them blood to drink. For it is just with you, that because they poured out the blood of your saints, they themselves drink blood. This means they suffer the vengeance of spilled blood, and those who, announcing good things to themselves, not only did not listen, but also cruelly destroyed, should not come into the knowledge of you. This is to be understood both of the Jews and of the Gentiles. For the Jews indeed poured out the blood of the holy prophets as they killed Ezekiel, and cut Isaiah, stoned Jeremiah. Hence, Stephen reproaches them in the contention he had with them, saying: Which of the prophets did not your fathers persecute? And they killed those who foretold the coming of the Just One. The Gentiles also similarly poured out much blood of the holy martyrs, as Nero crucified Peter, beheaded Paul, and many others. All these later drank blood by the just judgment of God, that is, they suffered the vengeance of blood: either in the present, as the Jews and Nero himself, so as to lose both this life and the future: or condemned in hell, and handed over to perpetual torments. Hence the Lord in the Gospel says: The blood of all the saints will be required from this generation of the wicked, which was shed upon the earth from the blood of Abel the just, even to the blood of Zacharias. Alternatively: The blood of the holy prophets is understood as the spiritual sense of them. Therefore, whoever has shed the blood of the prophets or other saints, that is, whoever has converted their spiritual sense into an earthly understanding, will drink blood, that is, will suffer the vengeance of blood. That is, whatever seems to have life, will lose, and will remain in the carnal sense by the just judgment of God. For they are worthy. It is fitting, therefore, that he who did not want to drink spiritual wine, be sodden with the corruptions of vices as with bloods.

The key portion is the phrase, "The past tense is placed here for three times, that is, for past, present, and future. Who were holy, you are just and will be." (corresponding to: "Præteritum tempus positum est hic pro tribus temporibus, id est, pro præterito præsenti et futuro. Qui eras sanctus, justus es et eris.")

I agree with KTA that this is not Beza's reading. In fact, this is even farther from Beza's reading than that of Beatus/Tyconius. Instead of two verbs and holy as in the Greek and in Beatus/Tyconius, Haimo/Ps.-Haimo has one verb and holy.

Haimo/Ps.-Haimo, however, explains that the single verb tense is placed here for past, present, and future. Thus, he offers a paraphrase: "Who were holy, you are and were just."

The bizarre claim that "It appears as though the original commentary included the biblical text as conjectured by Beza," is untenable. The commentary has the text interspersed. The text has the past tense and the commentary explicitly notes that there is just a single tense. Thus, the claim that "whoever compiled the present edition of the commentary took the commentary section from the original commentary and took the biblical text from a faulty version of the Vulgate," just makes no sense. There are commentaries (usually where the commentary is separated from the text) where the text is changed, such that the text and commentary do not align. This is not one of those cases.

Remainder of KTA's comments seem to be based on the inaccurate translation. Further comment would seem to be redundant.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

1.5 Greek Fathers' Usage of "Kαι Ο Εσομενος"

There are at least two Greek fathers who used the phrase "ο... εσομενος" as a reference to a person of the Godhead. This is noteworthy because the Greek New Testament never uses the phrase "ο εσομενος" to refer to God outside of Revelation 16:5 as it appears in Beza. Christ in Revelation is elsewhere referred to as "ο ερχομενος (who is to come)" (Revelation 1:4, 1:8, 4:8 and 11:17).

Clement of Alexandria (3rd century) referred to God as "ο εσομενος" in The Stromata, Book V, 6:

"ἀτὰρ καὶ τὸ τετράγραμμον ὄνομα τὸ μυστικόν, ὃ περιέκειντο οἷς μόνοις τὸ ἄδυτον βάσιμον ἦν· λέγεται δὲ Ἰαού, ὃ μεθερμηνεύεται ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἐσόμενος."

"Further, the mystic name of four letters which was affixed to those alone to whom the adytum was accessible, is called Jave, which is interpreted, “Who is and shall be.”" (Christian Classics Ethereal Library)

Gregory of Nyssa (4th century) referred to Christ as "ο εσομενος" in On the Baptism of Christ:

"Κοσμήτωρ δὲ πάντως τῆς νύμφης ὁ Χριστὸς ὁ ὢν καὶ πρόων καὶ ἐσόμενος͵ εὐλογητὸς νῦν καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων͵ ἀμήν."

"And verily the Adorner of the bride is Christ, Who is, and was, and shall be, blessed now and for evermore. Amen." (Christian Classics Ethereal Library)

[Note: In a certain internet forum these facts have been called a "red herring" to the issue of whether "ο εσομενος" should be in Revelation 16:5. By definition a "red herring" is something that is not relevant to the issue and carries no probative value. If a hypothesis is made more likely by the existence of a fact than by the absence of the fact, that fact is not a red herring. The fact that Greek fathers used "ο εσομενος" is not a red herring because the fact suggests that the future participle of "ειμι", in reference to Christ, is not a novel invention of a sixteenth century Western European scholar. With proof of an ancient native Greek usage of "ο εσομενος", the hypothesis that John used the term is made more likely. The weight to place on this evidence is debatable, but it is a misnomer to call it a red herring.]

I I appreciate that KTA sees such usage as "noteworthy." I think that the evidence is noteworthy for a different reason. I think it's noteworthy that Revelation 16:5 is never cited according to Beza's wording. In a previous post (link to post), I carefully scrutinized all the extant usage of ἐσόμενος is the literature indexed by the Thesaurus Linguae Gracae (as of 2023-11-10) up to 1582. I included the usage of Clement of Alexandria, Gregory of Nyssa, Cyril of Alexandria, Ps.(?) Olympiodorus the Deacon, Euthymius Protasecretis, John Climacus, and Manuel Chrysoloras, Unsurprisingly, the most that could be said for any of the usages was that they could be classified as a "possible allusion" if we assumed that Revelation 16:5 as written by Beza was known. They could equally be allusions to Revelation 1:4 or 1:8, or even to Plato.

While I agree that it's technically not a "red herring," the fact that Plato (and others) used the word itself provides the smallest feather's weight.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

1.6 Four Theories of How "Ο Εσομενος" Could Become Corrupt

Many people are not satisfied with Beza's conjecture or the reasons thereof, or the notion that Latin commentators or Greek Fathers may have been familiar with Beza's reading. In the few literature available defending Beza's conjecture, there is usually no explanation as to how "ο εσομενος" could change to "ο οσιος". Without an adequate theory as to the mechanism of the corruption, it is difficult to defend the position that there is a corruption. This article proposes four theories to remedy this problem:

- Theory 1: John wrote "ο εσομενος" in nomen sacrum form

- Theory 2: Bad conditions gave rise to corruption

- Theory 3: A scribe harmonized 16:5 with 11:17

- Theory 4: A Hebraist imposed Hebraic style onto the text

Before considering these theories, it is important to understand the textual history of the book of Revelation and of Revelation 16:5 in particular. There seems to be the misconception that the book of Revelation was just as well preserved as the other books of the Bible and that Revelation 16:5 in the existing manuscripts all have the same reading. When we understand the troubled textual history of the entire book and of 16:5 in particular, the four theories and the reliance on a conjectural emendation may appear to be more plausible.

On this point, I must tip my hat to KTA. Most of the Pro-KJV material on this verse (excluding, of course, Nick Sayers) fails to address any mechanism to explain how - on the theory that εσομενος was original - that οσιος could come to be found in virtually all the manuscripts.

I also appreciate KTA's openness in the attempt to tear down the manuscript evidence for Revelation in order to make Beza's conjecture seem more probable.

This brings us to Section II.

II. Responding to "How a Conjecture may be Justified"

Under the topic of how a conjecture may be justified, KTA offers five main points, which I will address in turn.

2.1 The Book of Revelation was Thoroughly Corrupted Very Early

Conjectural emendations are justified if we know that the text we are dealing with has a history of extensive and early corruption. The book of Revelation is such a text. As a word of assurance, however, there is no need to doubt the integrity of the text of Revelation as we now have in the Textus Receptus. God has promised to preserve his word. Although the existing manuscripts are often in conflict with one another, we must remember that the existing manuscripts for the most part came to us through the High Churches of the Orthodox East and the Catholic West. There were, however, countless Christians throughout history who lived outside of these institutions. The evidence of corrupted manuscripts is very much a history of the textual transmission of the High Churches. We trust God that he has providentially preserved his word to us through other faithful Churches even while the High Churches were transmitting corrupt texts. We trust that God was able to preserve the true reading of Revelation 16:5 until the advent of the printing press during the Reformation.

Please read the article at the following link for a prerequisite to understanding the extent of corruptions in the Book of Revelation: Book of Revelation in the Textus Receptus

I don't plan to respond in detail to the further-linked article, nor to all the articles to which that article links. In summary, KTA's linked article highlights some (but certainly not all) of the many places where the KJV departs from the majority of Greek manuscripts in Revelation. For KTA, this is evidence of "the extent of corruptions." That may be true, but it is evidence of the weakness of the KJV in Revelation rather than of the manuscripts themselves.

It should be noted that KTA's arguments end up undermining the Reformation position that God preserved the New Testament in the original Greek. For example, in one of the articles to which that further-linked article links, "Aren't some Textus Receptus readings based on weak Greek manuscript evidence?" KTA states: "Thus where there is no problem with grammar or syntax, it is absolutely illogical to give more weight to readings in Greek manuscripts just by the virtue of them being Greek manuscripts."

While people are certainly welcome to their own positions, and KTA does not seem to make a pretense of being part of the so-called "Confessional Bibliology" group, KTA's position is a contradiction of Beza's own views and the views of the Protestant Reformation more broadly. Greek priority was one of their rallying points against the Roman Catholic Church.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

2.2 The Curious Case of "Οσιος" at Revelation 15:4 in Papyrus 47

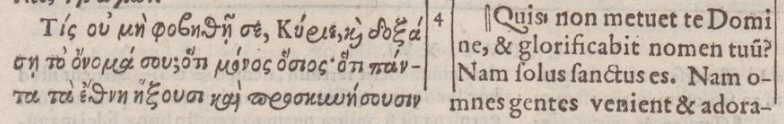

The word "Holy One" at Revelation 16:5 in all existing manuscripts is "οσιος". This word occurs one other time in the book of Revelation at chapter 15 verse 4. At Revelation 15:4, the Textus Receptus, Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus all read, "...και δοξασ(η)(ει) το ονομα σου οτι μονος οσιος οτι...." (...and glorify thy name? for thou only art holy: for....). The earliest manuscript of Revelation 15:4, however, omits "οσιος". P47 reads, "και δοξισει το ονομα σου οτι μονος ε̣ι̣ οτι...." (...and glorify thy name? for only if: for....).

P47: "και δοξισει το ονομα σου οτι μονος ε̣ι̣ οτι...."[EN1]

This is another example of a corruption in the existing manuscripts of the book of Revelation, and a relevant one at that because it involves the word in dispute at Revelation 16:5. If there is evidence of a scribal error involving "οσιος" at Revelation 15:4, it seems reasonable to suspect a scribal error involving the same word just one chapter later at Revelation 16:5. If critics of Beza's emendation at Revelation 16:5 simply acquaint themselves with the types of errors in the manuscripts of Revelation, they would not be so quick to judge the notion that conjectural emendations might be necessary to restore original readings in a very corrupt body of manuscript evidence.

[EN1: Kenyon, Frederic G. The Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri: Descriptions and Texts of Twelve Manuscripts on Papyrus of the Greek Bible. London: Emery Walker Ltd., 1933, 1937.]

I have no issues with KTA's image, but I provide my own, which might be slightly higher resolution:

The transcription of lines 10-11 of this sheet are as follows:

10| τις σε ου μη φοβηθη κε και δοξισει το ονο

11| μα σου οτι μονος ε̣ι̣ οτι παντα τα εθνη η

INTF has transcribed nearly 100 Greek manuscripts of Revelation 15:4. Among those transcribed manuscripts, P115 and P47 are the oldest that include any part of the verse. P115, unfortunately, does not include this part of the verse. P47 (incorrectly) omits οσιος from Revelation 15:4. Other early manuscripts (e.g. 1, 2, and 4) have "... το ονομα σου οτι μονος οσιος ..." (thy name because [you] alone [are] holy). Many of the Greek manuscripts, particularly the later Greek manuscripts, substitute a different word for holy, αγιος (hagios) for οσιος (a phenomenon that we saw to a lesser extent at Revelation 16:5) . Around four other manuscripts positively read εἶ (thou art) before the "holy" and about 20 read manuscripts positively read εἶ (thou art) after the "holy," as opposed to implying it. Beza's Latin makes the "thou art" explicit. Scrivener's TR omits the εἶ (thou art), presumably reasoning that the King James translators were following Beza's Latin translation of Beza's Greek, rather than the minority of manuscripts that have an explicit εἶ (thou art), as Stephanus did not note the presence of εἶ (thou art), despite noting αγιος (hagios) for οσιος (hosios). On the other hand, the Complutensian Polyglot has the explicit εἶ (thou art) and follows αγιος (hagios) rather than οσιος (hosios).

The "Pure Cambridge Edition" of 1900 has italics for "thou art," consistent with Scrivener's TR. However, the KJV 1611 did not have italics here. Based on the Textus Receptus Bibles site, I believe that the Oxford KJV 1769 likewise italicizes "thou art", although I've been cautioned about relying too carefully on that site (TR Bibles, KJB Online, STEP Bible).

The bottom line is that the KJV translators certainly could have known of the variant reading of an explicit εἶ (thou art) and could have followed that, or they simply could have been following Beza's Latin translation of the Greek. Even more simply, they could have been following Tyndale's original English translation in the form presented in the Bishop's Bible ("Who shall not feare thee O Lorde, and glorifie thy name? for thou only art holy: And all gentiles shal come and worship before thee, for thy iudgemetes are made manifest."). Indeed, it could be some combination of the above. It is an interesting question whether "TR only" types think that εἶ (thou art) is original.

Returning to P47 and Revelation 15:4, I note that P47 does have the explicit εἶ (thou art), yet stands alone (at least in the manuscripts transcribed by INTF) in omitting some form of "holy" here. Hoskier likewise does not report any such variant as is found in P47 here (link to Hoskier).Considering that P47 stands alone, it hardly seems fair to characterize this as a "corruption in the existing manuscripts" (i.e. plural manuscripts). Even if this can be justified because a corruption of one manuscript is somehow a corruption in the collection of manuscripts, KTA's next statement is a step farther in the wrong direction. KTA states: "If there is evidence of a scribal error involving "οσιος" at Revelation 15:4, it seems reasonable to suspect a scribal error involving the same word just one chapter later at Revelation 16:5." While it is certainly reasonable to look for and assess the possibility of scribal error, the bare fact that the same word in the previous chapter was subject to an omission in a single manuscript does not seem to be a reasonable basis for doubting the testimony of the overwhelming majority of manuscripts at Revelation 16:5, which has even less variation regarding the word "οσιος" than was found at Revelation 15:4.

Finally, while I appreciate KTA's assertion: "If critics of Beza's emendation at Revelation 16:5 simply acquaint themselves with the types of errors in the manuscripts of Revelation, they would not be so quick to judge the notion that conjectural emendations might be necessary to restore original readings in a very corrupt body of manuscript evidence." This is probably one of those bell-shaped curves. When you don't know about the variants, you don't see the need for conjecture. When you start to learn about variants, you see need for conjecture, but then when you become very familiar with variants, you no longer see the need for conjecture. That's probably an oversimplification of things. That said, many of the folks behind the NU text do not in principle oppose conjectures, yet there are very few conjectural emendations permitted in the text, even by those folks. My own reason for opposing conjectural emendations is based on a doctrine of preservation taught in Scripture, not based on my evaluation of the manuscripts.

Nevertheless, I think it is important to reiterate: the line of reasoning offered by KTA is available to those who deny providential preservation in the sense it was believed during the Protestant Reformation; it is much more difficult to square with the Reformation teachers (although some of them did seem to have room for conjectural emendation in rare cases).

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

2.3 There is a Related Textual Problem in Revelation 11:17

There is also a textual corruption at Revelation 11:17 that is related to Beza's emendation in Revelation 16:5. Please read the page, Should "and art to come" be in Revelation 11:17?, for more information on this textual variant. Nestle-Aland 27 has "ευχαριστουμεν σοι κυριε ο θεος ο παντοκρατωρ ο ων και ο ην" (we thank you Lord God Almighty, who is and who was). There is no "and who is to come". The Textus Receptus, however, has "ευχαριστουμεν σοι κυριε ο θεος ο παντοκρατωρ ο ων και ο ην και ο ερχομενος" (We thank you Lord God Almighty, who is and who was and who is to come). Here we see a similar situation as in Beza's Revelation 16:5 in which the Textus Receptus includes the mention of God's future aspect. The Textus Receptus reading is supported by Tyconius (4th century), 1841 (9th/10th century), 051 (10th century), 1006 (11th century), etc. (Nestle-Aland: Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th revised edition (2006)). The 1904 Patriarchal Text of the Greek Orthodox Church also has "και ο ερχομενος". The readings is also in the Clementine Vulgate: "Gratias agimus tibi, Domine Deus omnipotens, qui es, et qui eras, et qui venturus es".

This is a situation similar to Revelation 16:5 where the future aspect of God's existence is omitted in most manuscripts. Yet unlike Revelation 16:5, other Greek and Latin witnesses as well as Beza's Textus Receptus testify for the inclusion of the future aspect of God. If the future aspect of God should be the original reading of Revelation 11:17, there is manuscript evidence to support this. And if so, there is evidence that the mention of God's future aspect could be corrupted in the transmission of Revelation. This lends credence to the hypothesis that the mention of God's future aspect was likewise corrupted in Revelation 16:5.

Oddly enough I can agree with the words, though presumably not the intent, of KTA's opening sentence. There is also a textual corruption in the TR/KJV at Revelation 11:17 and it is related to Beza's reasoning. Beza mistakenly thought that "και ο ερχομενος" was found in each of Revelation 1:4, 1:8, 4:8, and 11:17.

The nearly 100 manuscripts transcribed by INTF show a strong majority of manuscripts lack "και ο ερχομενος" although an interesting minority has just "και".

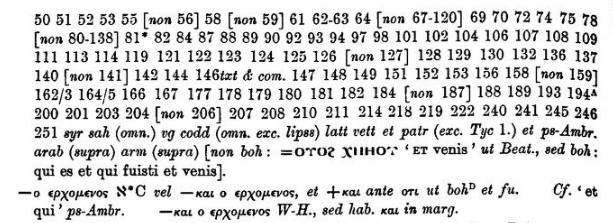

Hoskier has similar notes:

KTA's argument here relies on assuming that there was a loss of "και ο ερχομενος" rather than that there was an insertion of "και ο ερχομενος". The evidence points to the latter. The most natural source of such an insertion is a harmonization with phrases found in Revelation 1:4, 1:8, and 4:8. It is hard to explain how "και ο ερχομενος" would be lost in some many lines of transmission, including very early ones.

Moreover, KTA does not discuss the manuscript evidence at Revelation 1:4, 1:8, and 4:8. In those places, there is no similar issue with "και ο ερχομενος". Likewise, there is no similar issue with "και ο ερχομενος" in Revelation 16:5, where the manuscripts are essentially unified in not including any such reading. This makes an early harmonization error (for example, a mis-correction by an early scribe) the best explanation for the minority of manuscripts, versions, and patristic citations at Revelation 11:17 that have the longer reading.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

2.4 Evidence of Corruption Justifies Conjectural Emendations

In situations where the extent of corruption is so great that there is a likelihood that original readings may be lost in all existing manuscripts, judiciously applied conjectural emendations might be necessary in order to restore the original readings. The leading modern textual critic, Bruce Metzger, approved the use of a conjectural emendation as a valid method of textual criticism. He said:

"If the only reading, or each of several variant readings, which the documents of a text supply is impossible or incomprehensible, the editor's only remaining resource is to conjecture what the original reading must have been. A typical emendation involves the removal of an anomaly. It must not be overlooked, however, that though some anomalies are the result of corruption in the transmission of the text, other anomalies may have been either intended or tolerated by the author himself. Before resorting to conjectural emendation, therefore, the critic must be so thoroughly acquainted with the style and thought of his author that he cannot but judge a certain anomaly to be foreign to the author's intention." (The Text Of The New Testament at 182)

Bruce Metzger approved the method for “the removal of an anomaly” that is “foreign to the author's intention”. The conjectural emendation in Revelation 16:5 is justified because the majority reading in Revelation 16:5, “who is, and who was” followed by “that holy one,” is anomalous in not completing the declaration of God's past, present and future aspects, as is done in Revelation 1:4, 1:8, 4:8, 11:17*. Beza replaced "ο οσιος (that holy one)" with "και ο εσομενος (and shalt be)" to fix the anomaly. He said:

"But with John there remains a completeness where the name of Jehovah (the Lord) is used, just as we have said before, 1:4; he always uses the three closely together, therefore it is certainly "and shall be," for why would he pass over it in this place?" (Theodore Beza, Novum Sive Novum Foedus Iesu Christi, 1589. Translated into English from the Latin footnote.)

The appropriateness of Beza's conjectural emendation should be assessed in the context that Revelation was corrupted early and extensively, and today there are only 4 existing manuscripts of Revelation 16:5 from before the 10th century (as will be shown below).

1) We have already addressed the issue of the translation of Beza's annotations above. In this portion, the translation is less problematic than above, as can be seen from a comparison of the translations.

2) KTA is not following Metzger's guidelines for the use of conjectural emendation. The alleged "anomaly" is simply mentioning God's being in terms of past and present, but without reference to a future coming. Beza's solution to this perceived anomaly, however, is not to introduce "και ο ερχομενος" but to create a new anomaly by substituting "και ο εσομενος" for "και ο οσιος" in Stephanus/Erasmus' Greek text. While "ο οσιος" is the correct reading, it does not appear that Beza was aware of the existence, much less the frequency, of this reading.

Alongside this section, KTA asks: "Did you know? The guru modern textual criticism, Bruce Metzger, approved of conjectural emendations in principle." The short answer is that we do know. As discussed in my response to Thomas Holland (link), conjectural emendation is often used in the textual criticism of other books, particularly those that are weakly attested, such as those existing only in a single copy. That, plainly, is not the case with Revelation.

3) The idea that Revelation was corrupted early and extensively, such that it would require conjectural emendation to fix is not something that Metzger accepted, as is evidenced by his lack of acceptance of conjectural emendations into the main text. Instead, this overstatement of the degree of corruption appears to be motivated by a desire on KTA's part to excuse Erasmus and Beza for making unsupported changes to the text of Revelation. Whether so motivated or not, the argument lacks force. The alleged anomaly does not yield an "impossible or incomprehensible" reading. Moreover, rather than showing evidence of corruption, the manuscript evidence shows remarkable consistency. Furthermore, calling Jesus "the Holy One" is consistent with the author's intent and the context.

4) KTA makes a subtle but important shift. The phrase, "ο οσιος" is not problematic, so KTA does not focus on the actual reading. Instead, KTA tries to argue for the viability of Beza's conjecture. Considering whether the conjecture is a good fit to John's thought would only be relevant if we had a good reason to think that "ο οσιος" needed to be replaced.

Incidentally, the mere absence of a "future aspect" is not a reason to change "ο οσιος". Even if one believes that Revelation 11:17 originally included "και ο εσομενος," one finds that the difference amongst the manuscripts is simple omission (or insertion) of the phrase, not substitution. So, if the theory is that the triplet of explanations of YHWY ("Jehovah") should be present, that in itself does not suggest the removal of "ο οσιος". Someone trying to justify Beza has a very uphill battle. The person must (1) establish that Revelation 11:17 should have "και ο εσομενος," contrary to the majority of the evidence; (2) establish that Revelation 16:5 would be improper without completing the "is and was" with some future concept; (3) establish that the more obvious way of completing that grouping was not found here originally; and (4) establish some reason for thinking that "και ο εσομενος" was in fact the way that the grouping was originally completed.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

2.5 Conformity With Both Hebrew and Greek Thought

From a stylistic angle, the conjecture is justified on the basis that its phrasing conforms with both Hebrew and Greek thought. The formula in Beza's reading differs from the formula in Revelation 1:4, 1:8, 4:8 and 11:17* (having "shalt be" instead of "is to come"); but the phrase, "which art, and wast, and shalt be" is consistent with both Hebrew and Greek thought. As such, it is fitting for our Lord to use the phrase for the Hebrew and Greek audience of Revelation.

The Jerusalem Targum, written by Jewish Rabbis, refers to God as "He who Am, and Was, and Will Be" at Deuteronomy 32:39 (J.W. Etheridge, The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch. (1865), p. 669):

"When the Word of the Lord shall reveal Himself to redeem His people, He will say to all the nations: Behold now, that I am He who Am, and Was, and Will Be, and there is no other God beside Me:" (J.W. Etheridge, The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch. (1865), p. 669).

On the Greek side of things, there is an ancient poem believed to be sung by Dodonian priestesses, which refers to Zeus as the one who was, and is, and shall be. The poem is recorded by Pausanias in Description of Greece:

"The Peleiades are said to have been born still earlier than Phemonoe, and to have been the first women to chant these verses:–

Zeus was, Zeus is, Zeus shall be (Ζεὺς ἦν, Ζεὺς ἐστίν, Ζεὺς ἔσσεται); O mighty Zeus.

Earth sends up the harvest, therefore sing the praise of earth as Mother."

(Pausanias, Description of Greece (10.12.10), Translated by W. H. S. Jones)

The New Testament often took Greek philosophical words and formulas and applied them in Christian contexts. For example, John took the philosophically loaded word "Logos" and gave it a Christian meaning (John 1:1). Likewise, "which art, and wast, and shalt be" may have been intended as an allusion to the Greek song to Zeus. In adopting this formula, God is claiming that he alone is the true eternal God.

KTA's argument here could be strengthened by reference to Plato, as discussed above. That said, it is beside the point to inquire whether calling God the one who "shall be" or specifically "is, was, and shall be" is consistent with Hebrew and Greek thought. Considering that KTA is arguing that "και ο ερχομενος" indicates a "future aspect" of God, the three (or four, if you were persuaded that Revelation 11:17 included it) previous uses in Revelation would suffice to show that God having a "future aspect" of existence is also part of John's thought, not just Hebrew/Greek thought.

On the other hand, if "the coming one" is not enough, better than going to unbelieving Jewish interpreters and pagan Greeks, KTA could just go to the author of Hebrews:

Hebrews 13:8 - Jesus Christ the same yesterday, and to day, and for ever.

III. Response to "The Textual History of Revelation 16:5"

3.1 Only 4 Manuscripts of Revelation 16:5 Are From Before the 10th Century

A look at the textual history of Revelation 16:5 will show that the evidence against Beza's reading is not as strong as one might think. Although all known existing Greek manuscripts do not have "και ο εσομενος (and shalt be)," the body of evidence is relatively small and late, and even the existing evidence are not in full agreement with each other.Of all the ancient papyri that include the book of Revelation (P18, P24, P43, P47, P85, P98, P115), only P47 includes Revelation 16:5. Of all the ancient uncials (pre-10th century) that include Revelation (Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, Ephraemi, 0163, 0169, 0207, 0229, 0308), only Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Ephraemi include Revelation 16:5. Vaticanus does not have the book of Revelation at all. Thus the only witnesses from before the 10th century which include Revelation 16:5 are P47, Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus and Ephraemi. Just 4 manuscripts in 10 centuries is not a lot of evidence. There is definitely room to suppose that a reading with "και ο εσομενος (and shalt be)" existed in the early years of transmission, especially since Revelation in general was corrupted very early and an erroneous reading could have easily gained supremacy. Critics who say "There are over 5000 Greek manuscripts and not one of them has Beza's reading" are misrepresenting the situation. Although there are over 5000 Greek manuscripts, only a fraction has Revelation 16:5, and just 4 from before the 10th century. Since manuscript evidence (whether Alexandrian or Byzantine) is relatively scarce for Revelation 16:5 in comparison with other passages of scripture, the use of conjectural emendations is that much more justified for Revelation 16:5 than it normally would be for other passages.

1) It is true that there are only a small number of pre-10th century Greek manuscripts of Revelation. However, it is not as though the 10th century and later manuscripts just fell down from heaven. They are echoes of older copies. Furthermore, the small handful of pre-10th century Greek manuscripts are fundamentally consistent with the later manuscripts, particularly on this issue.

2) Additionally, we have an abundance of supportive versional and patristic evidence for the text that is supported by the extant Greek manuscripts. While some of the versional evidence may be ambiguous or not fully supportive of the Greek majority text, it all favors the Greek majority text over Beza's alteration.

3) I agree that a critic who says, "There are over 5000 Greek manuscripts and not one of them has Beza's reading" would be overstating the point. There are over 100 Greek manuscripts and not one of them has Beza's reading. I would likewise say that "Just 4 manuscripts in 10 centuries is not a lot of evidence," similarly overstates the case. First, from the first century to the 9th century is just 9 centuries. Second, the evidence during the first 9 centuries is not limited to the Greek manuscripts.

In a sidebar, KTA asks: "Did you know? Only 4 manuscripts of Revelation 16:5 exist from before the 10th century. The 3 earliest witnesses of Revelation 16:5 do not even agree." They agree in including οσιος and not including εσομενος or even ερχομενος. They disagree on other things, such as whether οσιος should have an article and whether or not οσιος should be connected to "righteous" with an "and".

The claim that "Revelation in general was corrupted very early" is an empty assertion, particularly when the main argument is about the alleged paucity of early evidence. It's an empty assertion because anyone with even a modicum of understanding of manuscript evidence knows that there are textual variants going back to the earliest manuscript copies not just in Revelation but in all books. It's also an empty assertion given that the level of variation in Revelation is only high when using the TR as a standard. The better explanation for that, however, is that Erasmus did not do as great work in Revelation as he did in other books, and that Beza's attempts to improve on Erasmus were not a uniform success.

The idea that we can use conjectural emendation because "manuscript evidence (whether Alexandrian or Byzantine) is relatively scarce for Revelation 16:5 in comparison with other passages of scripture" is not correct. The manuscript may be "relatively" less, but it is still quite abundant.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

3.2 Three Earliest Witnesses are Already Corrupt

The use of conjectural emendations is further justified because the three earliest witnesses of Revelation 16:5 already reveal corruption in this portion. Compare the portion in P47 (250 AD), Sinaiticus (350 AD) and Alexandrinus (400 AD) below (all readings are transcribed below in the same lower-case script for comparison purposes):

- "ο ων και ος ην και οσιος" (P47)

- "ο ων και ο ην ο οσιος" (Sinaiticus)

- "ο ων και ο ην οσιος" (Alexandrinus)

Papyrus 47

(Image source: See footnote 1)

P47: "...KAI OC HN KAI OCIOC (...and which wast and holy one)"

Codex Sinaiticus

(Image source: See footnote 2)

Sinaiticus: ""O ΩN KAI O HN O OCIOS (which art and which wast that holy one)"

Codex Alexandrinus

(Image source: See footnote 3)

Alexandrinus: "O ΩN KAI O HN OCIOS (which art and which wast holy one)"

The phrase gets shorter with the passage of time. The earliest reading from 250 AD says, "και οσιος" (P 47). Then by 350 AD scribes changed "και" to "ο" and the phrase became "ο οσιος" (Sinaiticus). Then by 400 AD scribes dropped the "ο" and the phrase became "οσιος" (Alexandrinus). Thereafter the Byzantine manuscripts vary between "οσιος" (as in Alexandrinus) and "ο οσιος" (Robinson/Pierpont Byzantine Text 2005). Consider the gradual change of the text with the passage of time:

- "και οσιος" (250 AD)

- "ο οσιος" (350 AD)

- "οσιος" (400 AD)

This variant is evidence that scribes either edited this phrase to tweak the grammar or were careless in copying this phrase. It is reasonable to doubt the integrity of the text in all existing manuscripts. The Greek texts of Erasmus 1522 and Stephanus 1550 have "ο ων και ο ην και ο οσιος." These texts agree with P47 and other manuscripts such as 1006, 1841, 2053 and 2026 in having "και" before "οσιος" (Nestle-Aland: Novum Testamentum Graece, 27th revised edition (2006)). Since P47 and other manuscripts have "και," Beza only replaced "οσιος" with "εσομενος.

Now that it has been established that the book of Revelation was corrupted early and extensively, and that the earliest manuscripts which do have Revelation 16:5 are corrupt, it is time to consider the four theories as to how "και ο εσομενος" (and shalt be) could have been the original reading.

1) Dealing with the last first, it has not been "established" but merely asserted that "Revelation was corrupted early and extensively." The textual data shows otherwise. There are minor differences amongst the copies, but minor differences are not equivalent to "extensive corruption."

2) The assertion, "The phrase gets shorter with the passage of time," is an example of an attempt to fit the data to a linear assumption about the text. This assumption might seem like a reasonable fit at first glance. However, once we review the variants found in the later manuscripts, the idea of a linear progression goes out the window. Additionally, the evidence from versional and patristic citations does not support the linear progression theory. Moreover, the evidence of the text of other New Testament books shows us that a linear progression of the text is not an accurate model for the textual transmission. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, while "ο οσιος" is fewer characters than "και οσιος," it is the same number of words, just one of the words is different. Furthermore, in the one different word, there are no overlapping letters. So, a model of linearly dropping words or characters is not a good fit, even to the data cited by KTA.

3) Recall that KTA previously mentioned "four" pre-10th century manuscripts. Why ignore the fourth in this analysis? In one way, it would be broadly supportive of KTA's comment, as the reading of Alexandrinus and of Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus are the same, and from about the same time. That said, the linear model of textual transmission is not accurate.

IV. Response to "Theory 1: John wrote "Ο Εσομενος" in Nomen Sacrum Form"

4.1 Nomina Sacra

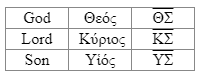

Nomina sacra (singular: nomen sacrum) are sacred names or titles of God which were often abbreviated in early manuscripts (Comfort, Philip W. and Barrett, David P. The Text of the Earliest New Testament Greek Manuscripts. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale House. (2001), pp.34-35). Examples include:

The common features of nomina sacra are (1) an abbreviation; and (2) a line above the name. It is surprising to see some of the words which scribes wrote as nomina sacra. Even remotely divine words such as "cross", "Israel", and "Jerusalem" were sometimes written as nomina sacra. In P75 at John 3:8, both the noun, "πνεῦμα" (wind) and the verb, "πνεῖ" (blows) are written as nomina sacra (http://thequaternion.blogspot.com/2011/02/p75-and-nomina-sacra.html). This peculiar nomen sacrum at John 3:8 was not carried over in future manuscripts. However, it goes to show that just about anything that is remotely divine qualified as a nomen sacrum.Although some scholars believe that nomina sacra were invented by later scribes, there is a possibility that the original writers of the New Testament were the originators of some of the more common nomina sacra (Philip Comfort, Encountering the Manuscripts: An Introduction to New Testament Paleography and Textual Criticism, (2005) p. 10). Perhaps the Apostle John himself wrote the words that refer to God in "κυριε ει ο ων και ο ην και ο εσομενος" (O Lord, which art, and wast, and shalt be) in an abbreviated nomina sacra form.

"Ων" (are), "ην" (was) and "εσομενος" (shall be) are conjugations of the verb "ειμι" (am), which is a suitable nomen sacrum. In Exodus 3:14, we read, "And God said unto Moses, I AM THAT I AM" (KJV). God's most sacred name is the great "I AM". This verse in the Greek Septuagint is, "καὶ εἶπεν ὁ θεὸς πρὸς Μωυσῆν Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν" (LXX). The following Orthodox art is an example of "ο ων" being used as Christ's divine name or title. Notice the nomina sacra for "Jesus" and "Christ" on each side of Christ's halo, which contains "ο ων" with the individual letters dispersed in three quadrants):

See the image at http://www.bethel-ucity.org/images/1025-5264a.jpg

[image not in the article, and not reproduced here]

(Image by Bethel Lutheran Church, University City, Missouri)

It is clear that at least "ο ων" in Revelation 16:5 is an indisputable nomen sacrum. The other forms of the verb in the phrase, "ο ων και ο ην και ο εσομενος" are also part of God's divine name. The Jerusalem Targum, written by Jewish Rabbis, refers to God as "He who Am, and Was, and Will Be" at Deuteronomy 32:39:

"When the Word of the Lord shall reveal Himself to redeem His people, He will say to all the nations: Behold now, that I am He who Am, and Was, and Will Be, and there is no other God beside Me:" (J.W. Etheridge, The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch. (1865), p. 669).

Clement of Alexandria and Gregory of Nyssa also referred to God as "ο εσομενος" (see above). If it were customary for Jews to refer to God as "He who Am, and Was, and Will Be", John may have written the entire line, "ο ων και ο ην και ο εσομενος" as a triadic string of nomina sacra. He may have written the line as:

ΟΩΝКАІΟΗΝКАІΟЄC

In nomen sacrum form, "ο εσομενος" might be abbreviated as OЄC. In context where the present participle and the imperfect are mentioned together in sequence, the mere two letters "ЄC" may suffice to indicate the future participle of "ειμι". In fact, in the Codex Sinaiticus it appears as though the place where "OOCIOC" now appears may have contained a three-lettered word. Sinaiticus has two full-sized Omicrons followed by "CIOC" all made to fit in the space of just one letter:

"O OCIOC" in Codex Sinaiticus

John may not have foreseen that the meaning of the abbreviation might be lost in future transmissions of the text. However, if the middle line in the rounded Epsilon of ΟЄC disappeared and the character became a Sigma, the word may have changed to ΟCC. A scribe who saw this may have thought ΟCC to be a nomen sacrum abbreviation of ΟCΙΟC (Holy One). Such a mistake is reasonable because ΟCΙΟC, meaning "Holy One", is also a suitable nomen sacrum. Furthermore, if "КАІOЄC" changed to "КАІOCIOC", there is a reasonable explanation as to why P47 says, "και οσιος" rather than "και ο οσιος".

A critic might point out that if the words "ΟΩΝКАІΟΗΝКАІΟЄC" were written in nomina sacra form, the words ought to have overlines just as we see in other nomina sacra. Yet, how would such overlines disappear from every manuscript? This problem could be overcome if we suppose that the nomina sacra form as we know today developed in two steps. Perhaps the original writers wrote nomina sacra in abbreviated form without any overlines. Then, later scribes may have invented the practice of adding overlines to make the nomina sacra more prominent. Perhaps the later scribes added overlines above words such as "Jesus" and "God" but did not think to add overlines above "OΩΝ" or "OЄC". As we have yet to fully understand the origin of the nomina sacra form, this is a possible hypothesis. Perhaps there were no overlines over "ΟΩΝКАІΟΗΝКАІΟЄC" to begin with.

1) I credit this section of the article with the inspiration that led to Nick Sayers' book. It is not the same argument Nick presented, but I believe it sparked some ideas that led to Nick's theory and ultimately to his book.

2) It is interesting to note that "ο ων" is used as a title of Jesus in Byzantine religious art (i.e. "icons"). As such icons are inappropriate, I reproduce only a censored version below. Nevertheless, in the censored image you can see "ο ων" inscribed within the figure's halo.

3) When KTA asserts, "It is clear that at least "ο ων" in Revelation 16:5 is an indisputable nomen sacrum," we should offer some pushback. The "IC" and "XC" abbreviations in this image are examples of what are called "nomina sacra" style abbreviations, as distinct from other kinds of abbreviations, such as suspension (e.g. "Imp." for Imperator or "Caes." for "Caesar", where only the first few letters are provided), acronym (e.g. ἰχθύς (Ichthus), which takes suspension to the next level by using initial letters of multiple words to form a word - in this example, Ἰησοῦς Χρῑστός Θεοῦ Yἱός Σωτήρ, meaning "Jesus Christ, God's Son, Savior," or ligature, such as the Omicron Upsilon ligature, ȣ shown twice on the right side of the icon, where two or more letters are combined into a single symbol). The letters O ω N are not examples of what are called "nomina sacra" abbreviations. They are a spelling out of the Greek phrase "ο ων" (with the nu shaped like a capital N rather than a lower case v).4) If what KTA means is that "ο ων" is a phrase that is used a title of God, this can be established contextually, without reference to later Byzantine idolatry. In the same way that "ὁ σωτὴρ τοῦ κόσμου" (shown in two parts above the shoulders in the icon) i.e. "the savior of the world" is a title of God, so also is "ο ων" (the being one). For evidence of the former, we can go to John 4:42, where that title is used by the Samaritan acquaintances of the Samaritan woman to refer to Jesus. Similarly, the phrase "ο ων" is used of God in Rev. 1:4, 1:8, 4:8, 11:17, and 16:5.

5) The phrase "ο ων" is likewise used specifically of Jesus in Romans 9:5, 2 Corinthians 11:31, and Revelation 5:5 (although it is not treated as a title there in the KJV). John uses the phrase in John 1:18, John 3:13, John 3:31, John 6:46, John 8:47, John 12:17, and John 18:37, all of which are just treated as ordinary uses in the KJV, but some of which could be understood as references to Jesus' divine nature, akin to the phrase "I am." Indeed, as KTA noted the first use of the phrase "ὁ ὤν" in the Septuagint is as part of the phrase, "ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ ὤν" (I am the being one). Moses is told by God to tell the children of Israel that "ὁ ὤν" (the being one) has sent him to them.

6) So, on the one hand, the phrase is a title of God, although it can also be used in an ordinary sense. It's hard to tell how many of the Johannine uses are intended to be allusions to Exodus 3:14, but this is a point worthy of further consideration.

7) The phrase "ὁ ἦν" is not a participle, but instead is an imperfective indicative. It is not often used as a title for God, apart from Revelation 1:4, 1:8, 4:8, 11:17, and 16:5, but is used to refer to Jesus as the initial words of John's first epistle: "Ὃ ἦν ἀπ᾽ ἀρχῆς" (Who has been from the beginning ...). It is also used to refer to the Beast in Revelation 17:11, "τὸ θηρίον ὃ ἦν καὶ οὐκ ἔστιν" (the Beast, the one has been and is not ...).

8) The phrase "ὁ ἐρχόμενος" (the coming one) is used of God in Revelation 1:4, 1:8, and 4:8. The phase is also applied to Jesus in Matthew 11:3, Matthew 21:9 (quoting Psalm 118:26), Matthew 23:39 (quoting Psalm 118:26), Mark 11:9 (quoting Psalm 118:26), Luke 7:19-20, Luke 13:36 (quoting Psalm 118:26), Luke 19:38 (quoting Psalm 118:26), John 6:14, John 12:13 (quoting Psalm 118:26), and Hebrews 10:37. Psalm 118:26 (Septuagint numbering 117:26) uses the phrase.

It is also used in a more usual sense in 2 Samuel 2:23 (Septuagint), Luke 6:47, John 6:35, and 2 Corinthians 11:4. Thus, like "ο ων" or "ὁ ἦν" so also "ὁ ἐρχόμενος" is used of God (and specifically of Christ) not only here in Revelation but elsewhere.

9) By contrast, the only time the word εσομενος appears in the Septuagint or New Testament is in Septuagint Job 15:14, which states: "τίς γὰρ ὢν βροτός ὅτι ἔσται ἄμεμπτος ἢ ὡς ἐσόμενος δίκαιος γεννητὸς γυναικός" "For who, being a mortal, can be without fault? Or who, being born of a woman, can be righteous?" It's hard to translate the future participle of "to be" in English, but the sense is something like, in the second half, "Or who shall ever be born of a woman and be righteous?" In context, Eliphaz is affirming the universal sinfulness of mankind, although perhaps in an interesting way this points us forward to the one and only exception, which is Christ.

10) Moreover, the phrase "ὁ ἐσόμενος" is never used as title of God. The closest exception would be the one statement by Clement of Alexandria, where he uses it as a part of the explanation of the meaning of Yahweh (alluded to above, and discussed at the link provided above).

11) Gregory of Nyssa is not an exception. Gregory's usage is a benediction similar to what we find in Romans 9:5 and 2 Corinthians 11:31.

Gregory: "Κοσμήτωρ δὲ πάντως τῆς νύμφης ὁ Χριστὸς ὁ ὢν καὶ πρόων καὶ ἐσόμενος͵ εὐλογητὸς νῦν καὶ εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας τῶν αἰώνων͵ ἀμήν."

Romans 9:5 - ὧν οἱ πατέρες καὶ ἐξ ὧν ὁ Χριστὸς τὸ κατὰ σάρκα· ὁ ὢν ἐπὶ πάντων θεὸς εὐλογητὸς εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας ἀμήν

2 Corinthians 11:31 - ὁ θεὸς καὶ πατὴρ τοῦ κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ οἶδεν ὁ ὢν εὐλογητὸς εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας ὅτι οὐ ψεύδομαι

It is an interesting question whether the KJV ought to have translated "ὁ ὢν" as a title, such as "the Being One" or the like. However, in point of fact, the KJV translates them as "who is" or "which is," not "the Being One."

Romans 9:5 - Whose are the fathers, and of whom as concerning the flesh Christ came, who is over all, God blessed for ever. Amen.

2 Corinthians 11:31 - The God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, which is blessed for evermore, knoweth that I lie not.

Likewise, Gregory: "And verily the Adorner of the bride is Christ, Who is, and was, and shall be, blessed now and for evermore. Amen." Gregory of Nyssa, On the Baptism of Christ

The "and was and shall be" is just a pious expansion of the "is" in the doxological formula found in 2 Corinthians 11:31 and similar to that of Romans 9:5.

On this point, KTA has an interesting dilemma. KTA can claim that Gregory offers evidence for a titular use of ὁ ὢν (and by extension also of ὁ ... πρόων and ὁ ... ἐσόμενος) but in doing so would suggest that the KJV mistranslated Romans 9:5 and 2 Corinthians 11:31. On the other hand, the careful eye notes a distinction between Gregory and the Revelation uses. In Revelation, in each case, each verb is preceded by its own article, whereas Gregory has one article for all three. The use is different. As much as I would like to improve the KJV, I think the KJV may already be correct at Romans 9:5 and 2 Corinthians 11:31, though I am open to an argument to the contrary. Similarly, in 2 Corinthians 11:31 "blessed" is consider the object of the being verb. If this translation is correct, then likewise "blessed" is the object of "is, was, and shall be" in Gregory.

13) The weakness of this theory is not limited to these points. There are several additional problems with the nomina sacra theory.

First, as KTA seems to concede, no one knows exactly when nomina sacra abbreviation came to be used. The assumption of most attempts at reconstructing the New Testament is to assume that words were written out, not abbreviated. My personal theory is that nomina sacra was used during time of persecution to obscure certain words for which the Roman soldiers were looking to identify a document Christian. The nomina sacra abbreviation method left the word looking like a Greek numeral. This allowed the document to survive the persecutors.

Second, the development of nomina sacra abbreviations seems to have begun with a core group of 4 to 6 contracted words, and eventually to have expanded to about 15. While KTA is right that occasionally words outside the 15 list were abbreviated in the same manner, this is a rarity.

Third, one of the characteristics of the nomina sacra style of abbreviations is that an overstroke was used to indicate the abbreviation (and, as I have surmised, possibly also to give the word the appearance of being a number). In the one instance that KTA appeals to as potentially being a candidate for such an abbreviation, there is no such overstroke. KTA's supposition that maybe nomina sacra style abbreviations were originally done without overstrokes is pure speculation.

Fourth, we have not been presented with a single instance in which ἐσόμενος was ever so abbreviated, in any literature. As one will recognize, abbreviations are useful to the extent that they can be understood by the intended reader. However, one-off abbreviations are not useful in this way.

Fifth, we should acknowledge that it is possible that the New Testament authors themselves employed these abbreviations, as they are found even in papyri manuscripts. That said, we have no examples of any being verbs being so abbreviated. All fifteen of the usual list of nomina sacra are nouns (God, Lord, Jesus, Christ, Son, Spirit, David, Cross, Mother, Father, Israel, Savior, Human, Jerusalam, Heaven). KTA offers an interesting counter-example of a place where "blows" (a verb) is abbreviated in nomina sacra style. However, that is not the normal case.

Sixth, KTA's proposal that "In nomen sacrum form, "ο εσομενος" might be abbreviated as OЄC," is unreasonable. First, none of the usual nomina sacra style abbreviations incorporate the article into the abbreviation. Second, even if we assume KTA means that "εσομενος" might be abbreviated as ... ЄC," this too is unreasonable. The word, εσομενος, is an infrequently used word. The proposed abbreviation would be ambiguous with other Greek words even including other forms of εἰμί, such as εἴης. Thus, this seems very unlikely.

Seventh, John was a seer and was writing under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, who certainly did know the future. While OCC might seem like a reasonable abbreviation in the nomina sacra style for οσιος, adjectives were less often so abbreviated. Apparently, the word ἅγιος was abbreviated at least once as ας (source), so we should not say it is impossible that there could be an abbreviation for the less common οσιος as well. However, following a similar pattern, one would expect that to be ος.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

4.2 Theory 1: Conclusion

With the above being a possibility, the following chronological chart explains how the intended "και ο εσομενος" could have changed to "ο οσιος":

"КАІ ΟЄC" (100 AD)

John wrote "ο εσομενος" in nomen sacrum form

↓

"КАІ ΟCC" (100-250AD)

The middle line in the rounded Epsilon disappeared

↓

"КАІ OCIOC" (100-250 AD)

Scribes thought the nomen sacrum referred to "Holy One"

↓

"КАІ OCIOC" (250 AD)

As seen in P47

↓

"Ο ΟCΙΟC" (350 AD)

As seen in Sinaiticus

↓

"ΟCΙΟC" (400 AD):

As seen in Alexandrinus

While we can applaud the creativity of this chart, there is nothing to corroborate the first few critical steps of the process, and the linear model for the latter steps is plainly wrong. One advantage of this theory over some others that could be offered is that it aims to account both for the asserted loss of "the shall-being one" and the gain of "O Holy One."

V. Response to "Theory 2: Bad Conditions Gave Rise to Corruption"

5.1 Confirmable Transcription Errors

Scribes are known for making some strange transcription errors. Consider the following confirmable mistakes of the scribe of Sinaiticus:

- The proper reading in Revelation 10:1 is "ιρις" (rainbow). However, the original hand of Sinaiticus has "θριξ" (hair). Thus the original scribe of Sinaiticus wrote, "I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud with hair on his head."

- The proper reading in Revelation 21:4 is "πρωτα" (former things). However, the original hand of Sinaiticus has "προβατα" (sheep). Thus the original scribe of Sinaiticus wrote, "neither shall there be any more sorrow, nor crying, nor pain; for the sheep have passed away."

- The proper reading in Revelation 21:5 is "καινα" (new). However, Sinaiticus has "κενα" (empty). Thus the scribe of Sinaiticus wrote, "Behold, I make all things empty."

If a scribe could mistake "ιρις" for "θριξ," "πρωτα" for "προβατα," and "καινα" for "κενα," it is certainly reasonable to suppose that a scribe mistook "εσομενος" for "οσιος." The common feature of all these other confirmable mistakes is that the original reading and the erred reading can look fairly similar. For example, "ιρις" and "θριξ" share 2 same letters. "πρωτα" and "προβατα" share the same beginning and ending letters. "καινα" and "κενα" share the same beginning and ending letters. Likewise, "εσομενος" and "οσιος" share enough of the same graphic features that a careless scribe might mistake one for the other.

1) I actually don't agree with KTA's take. As for KTA's three examples, "hair on his head" is actually a lot less strange than "a rainbow on his head." Moreover, sheep passing away is much less odd than an adjective with no noun passing away. Finally, given the preceding verse about removing tears, death, and (the scribe thought) sheep, making things "empty" is at least as natural as making them "new." So, I don't think these are "strange transcription errors," I think they are quite natural transcription errors.

2) While I agree that there are some graphical similarities between "εσομενος" and "οσιος" they are not really that close. Likewise, I would think it more likely that the Sinaiticus scribe's errors selected for this example were phonic, rather than graphic, and the sound difference is greater with "εσομενος" and "οσιος" than with the given examples.

Turning to the next section of KTA's article:

5.2 Three Conditions That Could Give Rise to Erroneous Copying

Even if "ο εσομενος" was not written as a nomen sacrum, we can still provide a reasonable hypothesis as to how "ο εσομενος" could be confused as "οσιος". There are three conditions that could lead to a scribe mistaking "εσομενος" for "οσιος". They are:

- A poorly written text

- An abbreviated text

- A damaged text

We will consider each of these in turn:

5.2.1 Poorly Written Text

Scribes did not always write words clearly. Consider how confusing and barely legible the word "οσιος" appears in Sinaiticus:

The underlined portion reads: "O ΩN KAI O HN O OCIOS (which art and which wast that holy one)"

The last four letters of "ο οσιος" are scrunched together and barely legible

"ο οσιος" is difficult to read in Sinaiticus not because of any effect of age, such as fading, but because the letters are scrunched together. This word would have been just as difficult to read when the codex was still new. Considering that a scribe could write "ο οσιος" as illegibly as it appears in Sinaiticus, it is not unreasonable to suppose that a scribe who saw "ο εσομενος" in a condensed and barely legible form mistook it for "ο οσιος".

1) Sinaiticus is around 1700 years old. I suspect it was more legible when it was first written. Also, some of the lack of clarity may be due to distortion resulting from image compression of the image itself.

2) While I agree that the smaller letters are harder to read, the smaller letters at the right side of the column are a frequent feature of this manuscript. Someone reading the manuscript, therefore, would expect and take into account such miniaturization of the letters and pay greater attention, not less, in such circumstances.

3) While this specific effect is applicable to Sinaiticus, where "osios" happened to fall at the end of a line, there is no reason to suppose that "osios" usually fell at the end of the line, such that a similar effect would be seen in many other of the now lost exemplar manuscripts of the fourth century.

Turning to the next sub-section of KTA's article:

5.2.2 Abbreviated Text

There is even a possibility that a scribe used an abbreviation for ο εσομενος, which may have looked very much like οσιος. Abbreviations for the purpose of nomina sacra have been discussed above, but even ordinary words were abbreviated on occasions. An abbreviation may have been used to save space at the end of a line or page, for example. A subsequent copyist of a papyrus with that abbreviated form of ο εσομενος may have thought that it was οσιος. There is evidence that scribes had the tendency to abbreviate some common words. Consider the text of P47 and how the scribe adopted an unusual abbreviation for ανθρωπων at Revelation 9:15:

The underlined portion is from Revelation 9:15Sir Frederic G. Kenyon commented on this strange abbreviation. He says, "The very unusual (if not unique) abbreviation, αθν for ανθρωπων, occurs on fol. Iv, l. 19." (Preface to the Revelation portion of The Chester Beatty Biblical papyri : descriptions and texts of twelve manuscripts on papyrus of the Greek Bible). It would not be surprising if a scribe who abbreviated ανθρωπων as αθν also abbreviated ο εσομενος as something like ο εσμος, which could easily be confused with οσιος. Moreover, an abbreviation of ο εσομενος, such as ο εσμος, would have had a line above the abbreviation to indicate that it is an abbreviation. But lines also indicated nomina sacra ("sacred names"). Thus a scribe seeing "εσμος" with a line above it could have mistakenly read the word as "οσιος" because "Holy One" would be a suitable sacred name of God.

1) KTA does not make clear that the issue with this example of nomina sacra style abbreviation is not about whether anthropon (human) is abbreviated, but specifically how. There is a more common way to abbreviate anthropon, but this scribe did not follow that more usual way. As noted above, this is one of the 15 relatively commonly abbreviated words within the nomina sacra type abbreviation system, though not one of the core four to six words (God, Lord, Jesus, Christ, Son, and Spirit).

2) Although some authors speculate that the nomina sacra style abbreviations were space-saving techniques, I am not persuaded that this view is correct. The choice of words to abbreviate does not seem to have been based on frequency nor on length. Of course, such a view is possible.

3) I don't agree that "εσμος" would have "easily" been confused with οσιος. To begin to substantiate this theory, one would probably want to identify some case where "esmos" was an abbreviation for "esomenos" (KTA does not offer any) and/or some other place where an esomonos/osios substitution allegedly took place. Neither of those building blocks for this argument have been provided.

Turning to the next sub-section of KTA's article:

5.2.3 Damaged Text

Scribes using damaged manuscripts may have had to make their best guesses as to what the damaged portions contained. Beza had a manuscript that was damaged at Revelation 16:5. He said:

"The Vulgate, however, whether it is articulately correct or not, is not proper in making the change to "holy," since a section (of the text) has worn away the part after "and," which would be absolutely necessary in connecting "righteous" and "holy one." (Theodore Beza, Novum Sive Novum Foedus Iesu Christi, 1589. Translated into English from the Latin footnote.)