Matthew Everhard has video (link to video) in which he suggests that the historic Francis Turretin was not being honest in his defense of Johannine Comma (the longer reading at 1 John 5:7-8).

I note that Everhard is working from a different translation of Turretin than that found in P&R's publication, namely the Dennison translation. I don't know where he got that translation, but it is fairly accurate. Starting around 4:20 into the video, Matthew Everhard states (all transcriptions are lightly edited computer-generated transcripts):

4:20-5:03 (approximately)

It just so happens that this is either a wild overstatement or he is fudging the truth or he is stretching the truth or perhaps he just doesn't know what he's talking about here because look he says "all the Greek witnesses have it." Okay, so that's a universal positive. He's making a universal positive argument here by saying that they all have it. "The words always were of unquestioned truth" okay so that's a pretty dynamic statement there, "and are read in all the Greek manuscripts from the times of the Apostles themselves." Okay, now this would be probably the sentence that we have the most trouble with because as it turns out this is just factually not true.

I agree that it is not factually true.

6:19 to 6:59 (approximately)

Now, unfortunately this is a statement that is repeated very very often today especially by those who defend either the King James version which contains John's comma or by those who defend the textus receptus and a lot of people will point back to Turretin's statement here saying it's always been there and because Turretin is seen as a very reliable and trustworthy defender of reformed Orthodoxy this statement from him as taken as as good as gold as it comes to John's comma.

I agree that this does get trotted out by folks who totally disagree with Turretin's view on textual transmission.

10:15 to 11:43 (approximately)

And so for Francis Turretin to claim that John's comma is in all the Greek manuscripts, that is just wildly wildly inaccurate. It cannot possibly even remotely be considered accurate. It is essentially a false statement and this is the problem with making universal positives: it's in all of them or it's in none of them. It's so easy to disprove a universal positive or a universal negative because all you need is one example to the contrary to disprove the entire statement. So Francis Turretin tries to do too much here by fudging or stretching the data well well beyond the levels of truthfulness. Now one could possibly say that Turretin knew about a bunch of manuscripts that we don't have today and this is the argument that advocates of the Textus Receptus or advocates of the King James Version will commonly make. They'll say, "Well he was referring to the manuscripts that he knew of." Well where are they? Well apparently they've all gone out of existence because because of all of the myriads and myriads of plethora of manuscripts there's only this very very scant few that actually have John's comma and the oldest one with a comma in its text is from the 14th Century. Man alive, that is not great biblical support or manuscript evidence to support John's comma.

First, I would caution this "plethora" argument, unless you take the time to figure out how many Greek manuscripts of 1 John there are, because that is the first response by the more learned TR advocates.

Second, there is a more straightforward explanation for Turretin's claim.

11:54 to 12:48 (approximately)

Remember what Francis Turretin said here. He says -- "not the saying in first John 5:7, although some formerly called it into question and heretics do so today," so Turretin goes pretty far into the deep end of the pool here by saying that "formerly some called into question" that may be a reference to Calvin as we're going to see here and "heretics do so today" which again is a statement that a lot of people from the TR defense position or the King James version defense position they want to call people heretics because Francis Turretin said so well if that's true then I I guess Calvin is either one of those formerly who's just wrong here according to Turretin or he's one of those heretics as modern advocates might say.

I won't address his Calvin arguments, for a variety of reasons, but primarily because I think there is a better explanation, and Calvin's errors are different from Turretin's.

Once we understand Turretin's claim better, the heretics and "formerly some" will fall into place.

17:50 to 18:45 (approximately)

So, I think Turretin is trying to do too much. I get his point, he really does want to redress the Roman Catholic Arguments for the supremacy of the Latin Vulgate and he does so by making a great argument in general that we should rely on the Greek and the Hebrew not the Latin but this statement that we looked at today clearly he presses the boundaries of anything that could remotely even be considered true and again the argument of some modern advocates of the Textus Receptus and of the King James version that perhaps he had a just all these manuscripts they all had it and those just happened to be the one that poof disappeared from history somehow and that all that we're left with is all those plethora and myriads of manuscripts that don't have it except for one or two that were really late like yikes level late in terms of history here -- that's just not a great way to make that argument, okay? so easily testable.

This is starting to catch the correct line. Turretin is engaging Roman Catholic claims. By contrast, Everhard's material is probably aimed at something like this material from FBC Roy (link to video). So, Turretin is using Roman Catholic scholarly material against themselves.

Dennison's translation of Francis Turretin's Institutes, Volume 1, p. 115, states:

X. There is no truth in the assertion that the Hebrew edition of the Old Testament and the Greek edition of the New Testament are said to be mutilated; nor can the arguments used by our opponents prove it. Not the history of the adulteress (Jn. 8:1-11), for although it is lacking in the Syriac version, it is found in all the Greek manuscripts. Not 1 Jn. 5:7, for although some formerly called it into question and heretics now do, yet all the Greek copies have it, as Sixtus Senensis acknowledges: "they have been the words of never-doubted truth, and contained in all the Greek copies from the very times of the apostles" (Bibliotheca sancta [1575], 2:298). Not Mk. 16 which may have been wanting in several copies in the time of Jerome (as he asserts); but now it occurs in all, even in the Syriac version, and is clearly necessary to complete the history of the resurrection of Christ.

The original text (first edition) of Second Topic, Question XI, section X says:

Transcription:

X. Falso Editio Hebraea Vet. & Graeca N. T. dicitur mutila: Nec quae ab Adversariis afferruntur testimonia hoc evincere possunt; Non historia adulterae Io.8. licet enim desit in Syriaca Versione, reperitur in omnibus Graecis Codicibus. Non dictum 1. Io.5:7. quamvis enim quidam in dubium olim vocarint, & vocent hodie haeretici, habent tamen omnia Exemplaria Graeca, ut Sixtus Senensis agnoscit; verba indubitatae semper veritatis fuerunt, & in omnibus Graecis exemplaribus ab ipsis Apostolorum temporibus lecta. Non Marc 16. caput, quod potuit in variis exemplaribus defiderari tempore Hieronymi, ut ipse fatetur, sed nunc in omnibus habetur etiam in Syriaca versione, & est plane necessarium ad perexendam historiam resurrectionis Christi.

Translation:

X. It is falsely stated that the Hebrew edition of the Old Testament and the Greek New Testament are mutilated: The testimonies brought forth by the Adversaries cannot prove this; not the story of the adulteress in John 8, for although it is missing in the Syriac Version, it is found in all Greek Codices. Not the saying in 1 John 5:7. Although some have doubted it in the past, and heretics do so today, all Greek manuscripts, as Sixtus of Sienna acknowledges, contain it; these words have always been of undoubted truth and have been read in all Greek manuscripts since the times of the Apostles themselves. Not Mark 16, which might have been missing in various manuscripts in the time of Jerome, as he himself admits, but now is found in all, even in the Syriac version, and is absolutely necessary to completely narrate the story of Christ’s resurrection.

In short, I think Dennison's translation is perfectly fine and accurately conveys Turretin here.

Notice, however, that Turretin makes a claim about "all the Greek copies" of 1 John, based on the testimony of Sixtus of Siena (aka Sixtus Senensis).

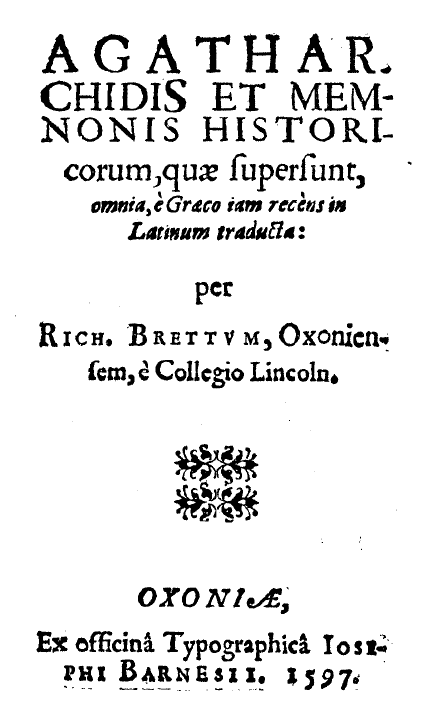

Moreover, look at what Sixtus Senensis said (Liber Septimus, p. 597B - this is not the same printing/edition referenced by Dennison, although it is the same Bibliotheca Sancta):

Transcription:

Ipsam vero primam Ioannis Epistolam, Anabaptistae contendunt, adscititiis additionibus falsatam, sumpto hinc argumento, quod in quinto eius capita addita sit sentnentia illa: Tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in caelo, Pater, Verbum, & Spiritus Sanctus: & tres unum sunt, quam sententiam eo in loco dicunt insertam a fautoribus Trinitatis, reclamantibus omnibus vetustis Graeciae exemplaribus, in quibus ea verba olim non fuisse, etiam Hieronymus in praefatione Canonicarum Epistolarum testatus est. Erasmus vero, qui in prima editione sua Novi Testamenti eam non habet, idcirco illam se praeteriisse affirmavit, quia in Graecis codicibus ea verba non legerentur.

Indeed, the Anabaptists contend that the first Epistle of John has been corrupted with spurious additions, drawing this argument from the fact that in its fifth chapter, the sentence has been added: 'There are three that bear witness in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one.' They claim this sentence was inserted in that place by supporters of the Trinity, contrary to all the ancient Greek manuscripts, in which these words were not originally found, as even Jerome has testified in the preface to the Canonical Epistles. Moreover, Erasmus, who in his first edition of the New Testament does not include it, stated that he omitted it because those words were not read in the Greek codices.

Ad vero, quod impii Anabaptistae, ac Servetani de verbis illis, quae in quinto capite primae Ioannis adiecta contendunt, respondemus, ea verba apud Catholicos indubitate semper veritatis fuisse, & in omnibus Graecis exmplaribus ab ipsis Apostolorum temporibus lecta: nec opus est quicquam de ipsorum perpetua integritate, synceritateque dubitare, cum Iginus Papa primus, inducat ea adversus Haereticos, tanquam invictum pro summa Trinitate testimonium. Sic enim in epistola ad omnes Christi fideles scribit: Et iterum ipse Ionnes Evangelista ad Parthos scribens ait: Tres sunt, qui testimonium dant in caelo, Pater, Verbum, & Spiritum Sanctus, & hi tres unum sunt. Quin & sancta mater Ecclesia testimonium istud quotannis per octavam Paschae in sacris mysteriis, ut ex vera & germana eiusdem Evanelistae Epistola decantat. Nec Hieronymus usquan dixit, illud in codicibus Graecis Ecclesiae Catholicae defuisse, immo in Prologo Canonicarum ad Eustochium, conqueritur, haec verba ab infidelibus, & Haereticis translatoribus in Latinum versa non fuisse, cum passim in Graecis voluminibus legerentur, haec verba ab infidelibus, & Haereticis translatoribus in Latinum versa non fuisse, cum passim in Graecis voluminibus legerentur, haec enim sunt Hieronymi eo in Prologo verba: Quae scilicet Epistolae, si ut ab eis, hoc est, Graecis authoribus, digesta sunt, ita quoque ab interpretibus fideliter verterentur in Latinum eloquium, nec ambiguitatem legentibus facerent, nec sermonum sese varietas impugnaret, illo praecipuem loco, ubide unitate Trinitatis, in prima Ioannis epistola positum legimus, in quo etiam ab infidelibus translatoribus multum erratum esse a fidei veritate comperimus, trium tantummodo vocabula, hoc est Aquae, Sanguinu, & Spiritus, in ipsa sua editione ponentibus, & Patris, Verbique, ac Spiritus Sancti, testimonium omittentibus, in quo maxime & fides Catholica roberator, & Patris, & Filii, & Spritus Sancti in una Divinitatis substantia comprobatur. Hec Hieronymus. Quod autem ex prima Erasmi traductione adijciunt, nihil nos movet viti huius Authoritatas, cuius non paucas sententias nuper catholica Ecclesia damnavit, cum ea verba in Graecis exemplaribus ut ostendimus, semper fuerint, & nunc quoque in nostris Graecis codicbus palam in hunc modum legantur, τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες, εν τῷ οὐρανῷ, πατήρ, λόγος, καὶ Πνεῦμα Ἅγιον καὶ οἱ τρεῖς ἕν εἰσιν Et ipsem et Erasmus in Annotationibus suis fateatur, haec eadem verba, haberi in pervetustis Graecis exemplaribus Britanniae, Hispaniae ac Rhodi.

To the truth, regarding the words that the impious Anabaptists and followers of Servetus contend have been added to the fifth chapter of the first Epistle of John, we respond that these words have always been undoubted truth among Catholics, and read in all Greek copies since the times of the Apostles themselves. There is no need to doubt their perpetual integrity and sincerity, since Pope Eugene I used them against heretics, as an invincible testimony for the supreme Trinity. Thus, he writes in his letter to all the faithful of Christ: 'And again, John the Evangelist himself writing to the Parthians says: There are three that bear witness in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost, and these three are one.' Moreover, the holy mother Church chants this testimony every year during the octave of Easter in the sacred mysteries, as from the true and genuine Epistle of the same Evangelist. Nor did Jerome ever say that it was missing in the Greek codices of the Catholic Church; on the contrary, in the Prologue to the Canonical [Epistles] to Eustochium, he complains that these words were not translated into Latin by unfaithful and heretical translators, although they were widely read in the Greek volumes. These are the words of Jerome in that Prologue: 'Which Epistles, if as they are composed by their Greek authors, were also faithfully translated by interpreters into the Latin language, they would not cause ambiguity to the readers, nor would the variety of words conflict with each other, especially in that principal place, where we read of the unity of the Trinity, in the first Epistle of John, in which we also find that much error has been made by unfaithful translators far from the truth of faith, only placing three words, that is, Water, Blood, and Spirit, in their own edition, and omitting the testimony of the Father, and of the Word, and of the Holy Ghost, in which the Catholic faith is particularly strengthened, and the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit are proved to be in one substance of the Divinity.' Thus Jerome. As for what they add from the first translation of Erasmus, it does not move us because of this Author's authority, whose not a few sentences the Catholic Church has recently condemned, since as we have shown, those words have always been in the Greek copies, and are now also plainly read in our Greek codices in this manner: τρεῖς εἰσιν οἱ μαρτυροῦντες, εν τῷ οὐρανῷ, πατήρ, λόγος, καὶ Πνεῦμα Ἅγιον καὶ οἱ τρεῖς ἕν εἰσιν. And even Erasmus himself admits in his Annotations that these same words are found in very ancient Greek copies of Britain, Spain, and Rhodes.

Stephanus 1550 (link to source)

If you were reading this textual apparatus, would you think what Turretin did, namely that all the Greek manuscripts have the text?