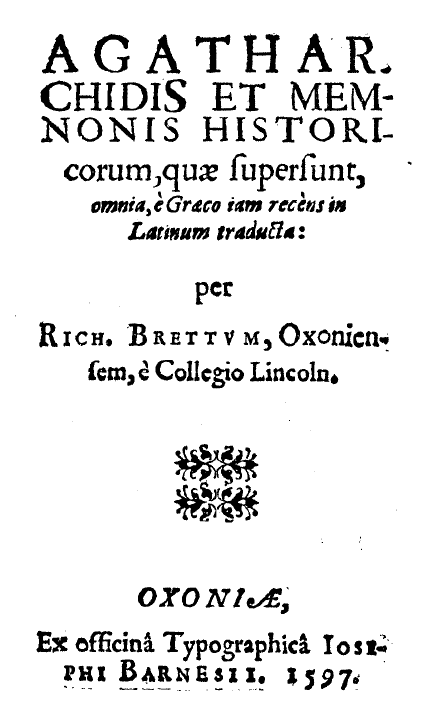

There are claims on the internet that Richard Brett (one of the KJV translators) had some knowledge of Ethiopic.

Oxford University provided the following biography (link to source) in Alumni Oxonienses 1500-1714.

Brett, Richard gent., born in London. Hart Hall, matric. 8 Feb., 1582-3, aged 15; fellow of Lincoln Coll., B.A. 12 Oct., 1586, M.A. 9 July, 1589, licenced to preach 16 July, 1596, B.D. 6 June, 1597, D.D. 13 June, 1605 (son of Robert, of White Stanton, Somerset), rector of Quainton, Bucks, 1595, one of the translators of the Bible 1604, one of the first fellows of Chelsea College 1616, died 15 April, 1637. See Ath., ii. 611; & D.N.B.

There is also a biographical sketch in The Translators Revived: A Biographical Memoir of the Authors of the English Version of the Holy Bible, by Alexander Wilson M'Clure (1853)(link to source).

This reverend clergyman was of a respectable family, and was born at London, in 1567. He entered at Hart Hall, Oxford, where he took his first degree. He was then elected Fellow of Lincoln College, where, by unwearied industry he became very eminent in the languages, divinity, and other branches of science. Having taken his degrees in arts, he became, in 1595, Rector of Quainton in Buckinghamshire, in which benefice he spent his days. He was made Doctor in Divinity in 1605. He was renowned in his time for vast attainments as well as revered for his piety. "He was skilled and versed to a criticism" in the Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldee, Arabic, and Ethiopic tongues. He published a number of erudite works, all in Latin. It is recorded of him, that "he was a most vigilant pastor, a diligent preacher of God's word, a liberal benefactor to the poor, a faithful friend, and a good neighbor." This studious and exemplary minister having attained this exalted reputation died in 1637, at the age of seventy, and lies buried in the chancel of Quainton Church, where he had dispensed the word and ordinances for three and forty years.

Although M'Clure does not seem to cite his source, it appears to come from Henry John Todd''s 1821 "Memoirs of the Life and Writings of the Right Rev. Brian Walton, D.D., Lord Bishop of Chester...with Notices of His Coadjutors in that Illustrious Work...and of the Authorized English Version of the Bible...to which is Added Dr. Walton's Own Vindication of the London Polyglot," which states (p. 117)

Dr. Miles Smith and Dr. Richard Brett, follow; the former so conversant and expert in the Chaldee, Syriac, and Arabic that he made them as familiar to him, almost, as his native tongue; and had Hebrew also at his fingers' ends: the latter, skilled and versed to a criticism in the Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldee, Arabic, and Ethiopic tongues.

That work also describes (p. 127):

Of similar rank was John Gregory, called the miracle of his age for critical and curious learning; having attained to a learned elegance in English, Latin, and Greek, and to an exact skill in Hebrew, Syriac, Chaldee, Arabic, and Ethiopic.

Thankfully, Todd does cite his source, which is "Athenae Oxonienses. An Exact History of All the Writers and Bishops, who Have Had Their Education in the ... University of Oxford from the Year 1500 to the End of the Year 1690. (etc.)" by Anthonya Wood (1691), vol. 1 (col. 517).

Note that in this biography, it was not until after he entered University in 1582 and got a degree in Arts that he become a fellow of Lincoln college where, "by the benefit of a good Tutor," he became "eminent in the tongues." Thus, it seems unlikely that he was in any way involved in assisting Beza for Beza's 1582 edition.

Richard Brett's translation included a section on the Rhinoceros (see the discussion here), further confirming that "rhinoceros" was not what the KJV translators intended when they wrote "unicorn".

"Eghzaibher" componitur ex "Eghzia" domino, "Ab" patre, "her" bono: quod est dominus pater bonus: ut illi Aethiopes, qui Romae habitant, interpretantur.

"Eghzaibher" is composed of "Eghzia" meaning lord or master, "Ab" meaning father, and "her" meaning good: which is 'good lord father,' as those Ethiopians who live in Rome interpret it.

The book is summarized thus:

Incidentally, Elias Hutter knew of the existence of the Ethiopian language, as such, and even of some origin myths of the language and people of Ethiopia, as evidenced here:

Another source, Bibliotheca apostolica vaticana a Sixto V. Pont. Max. in splendidiorem, commodioremq. locum translata, et a fratre Angelo Roccha a Camerino ... commentario variarum artium ... illustrata, by Angelo Rocca (1591), describes the conventional knowledge of the subject at that time:

It may not be a lot, but it shows a basic familiarity with the language, even before the 1548/9 Ethiopic Bible was printed. Incidentally, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, Sebastian Munster was a Hebraist and former Franciscan who became Lutheran around 1529. His tombstone described him as "the Ezra and the Strabo of the Germans."

Regarding knowledge of Aethiopic during the 14th through 17th centuries, I found an interesting article by Dejazmatch (ደጃዝማች, Commander or general of the Gate) Zewde Gebre-Sellassie (1926-2008) who was not only a deputy prime minister in Ethiopia, but also earned a PhD from Oxford. In the 1996 article, Dr. Gebre-Sellassie explains (source - notice the source seems to be an OCR result, and consequently contains numerous typographic errors):

In the middle of the 14th century (1351) some Ethiopians began coming to Rome through the Holy Land and in 1441 during the Council of Florence Abba Niqodimos, the Abbot of the Ethiopian monastery of Jerusalem, is said to have sent a delegation of Ethiopian monks. The number of Ethiopian pilgrims in Rome gradually increased during the papacy of Sisto IV (1471-1484). At that time the Church of Santo Stefano in Vaticano (St Stephen within the wall of the Vatican) and the adjoining hospice were granted by the Pope to the Ethiopian pilgrims. This property remains to this day in their possession, known as San Stefano dei Mon or degli Abissini (St. Stephen of the Abyssinians).The Ottoman Turks occupied Syria and Palestine in 1516, Egypt in 1517; and Ethiopia was in a turmoil by the Islamic Jihad during the First half of the Sixteenth Century. During this period the Ethiopian monks in Jerusalem were in a desperate situation and many of them joined the different Catholic orders, such as the Franciscans and the Benedictines some of them migrated to Southern Europe, to Austria, Spain and mostly to Italy.Some of these monks were eminent scholars well versed in Ethiopian languages, history and culture as well as theology and philosophy. Among those who settled at San Stefano in the Vatican, the most outstanding scholars who deserve special mention, are the following: Abba Tomas of Waldiba; Abba Tesfa Tsion Mallizo, who was commonly known in Rome as Pietro Indiano - Peter the Indian; Abba Gorgorios of Mekane Sellassie and, later on during the 19th Century, Debtera Kifle Giorgis.Abba Tomas of Waldiba, who called himself son of Samuel, after the patron saint and founder of his monastery, was the pioneer in the scholastic endeavor of teaching the Geez alphabet and grammar in Europe. Among his students was the German scholar Johannes Potken, who for the first time printed the Psalms of David in Geez on June 30th, 1513.Abba Tesfa-Tsion Mallizo, known in Rome as Pietro Indiano (Peter the Indian), is referred to as erudite and full of humility and love. He had published the New Testament in Geez in 1548-1549. He also translated the Anaphora of the Apostles and the Baptismal prayers of the Ethiopian Church into Latin, with the help of two Italian scholars, Paolo Giovo and Pietro Gualtieri who was a polyglot and secretary to the Pope. Subsequently, with the help of Mario Vittorio di Rieti (who later became a bishop of his native region Rieti) he published a grammar of the Geez language and a list of Ethiopian sovereigns. Abba Tesfa Tsion came from Jerusalem to Rome in 1538 and stayed there for twelve years. He died in Tivoli at the age of forty-two in 1550.Among the well known Europeans who were instructed by the Ethiopian monks were Atanasio Kircher and Jacobus Wemmers, the author of the first Geez or Ethiopic-Latin dictionary during the first half of the 17th century. The Danish scholar Theodor Peter, who edited a number of Ethiopian studies and the Dominican Maria Wansleb, are also credited for considerable achievements.However, no one has profited and utilized his learning as much as Hiob Ludolf, the German scholar who was instructed by Abba Gorgorios or Gregory of Mekane Sellassie, assisted for translation from Amharic to German by D'Andrade Antonio, son of a Portugese father and an Ethiopian mother. Ludolf's Grammatica Aethiopica (1661), Historia Aethiopica (1681), which was translated into English, French and Dutch; Commentary on the History (1691), Grammatica Linguae Amharicae (1698), and Lexicon Aethiopico - Latinum (1661) became the standard authoritative texts for teaching Ethiopian studies in European universities and centers of learning until Dillmann's monumental works in the nineteenth century published between 1847 and 1894, notably his Lexicon (1865) and Grammar (in 1857 in German, English translation in 1907), as well as the Ethiopian version of the books of Enoch (1851), Jubilees (1859), Ascencion of Isaiah (1877), and the Histories of Arride Tsion and Zera Yacob (1884).

No comments:

Post a Comment